Doug Daigle plays a key role in efforts to shrink the size of the "dead zone," the annual low-oxygen area off Louisiana's coast.

As coordinator of the Louisiana Hypoxia Working Group, the LSU research scientist oversees a forum for state and federal officials, researchers and stakeholders on the topic. He has been involved since 2003 in the multi-state program to reduce the nutrients entering the Mississippi River Basin that cause the dead zone.

Doug Daigle asked the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority on July 12, 2023, to place more emphasis on the state's efforts to reduce nutrients in the Mississippi and Atchafalaya rivers to assist in reducing the size of the low-oxygen dead zone along the state's coastline. (Louisiana Legislature)

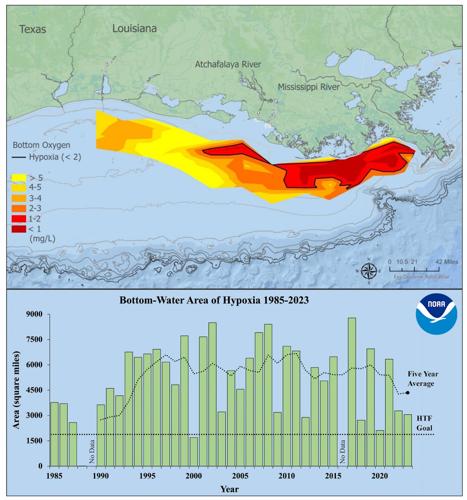

The zone was measured at 3,058 square miles in August 2023, representing a five-year average of 4,347 square miles, more than two times larger than a reduction goal set for 2035. The Times-Picayune | The Advocate talked to Daigle in an interview edited for length and clarity.

What is the “dead zone”?

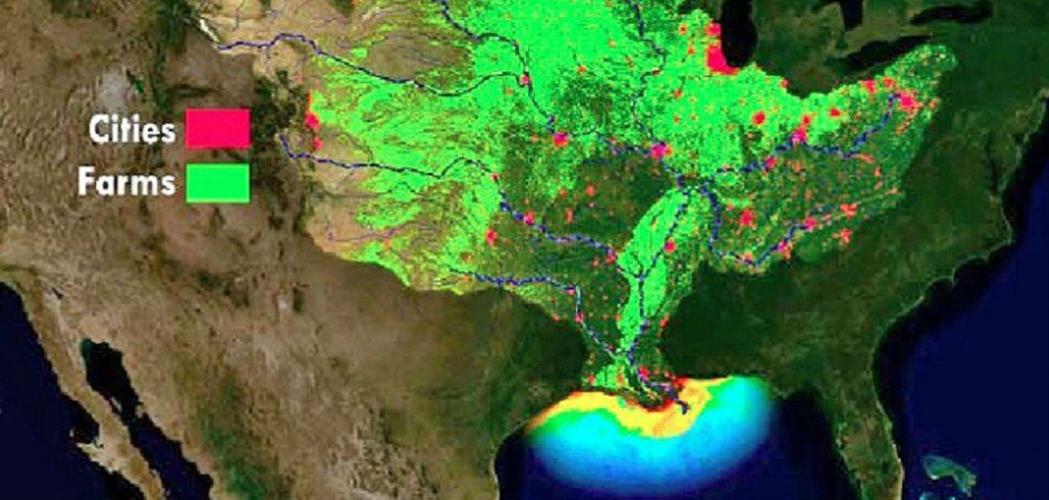

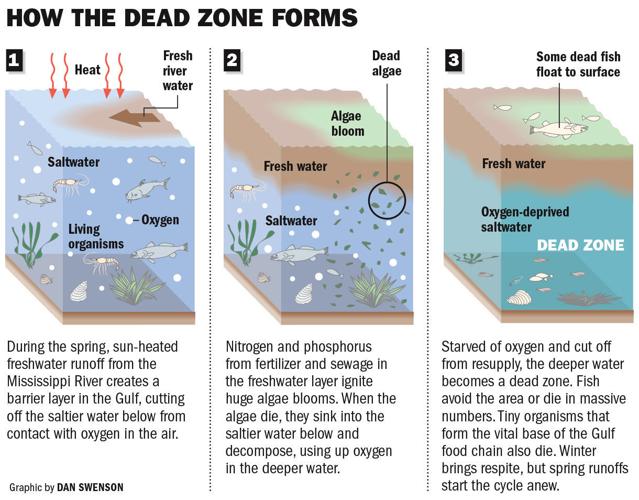

Every year, this area of low oxygen forms offshore along the coast of Louisiana. It’s fueled by nutrients in the Mississippi and Atchafalaya rivers, and because of the prevailing currents along the shoreline, it forms west of the mouth of the Mississippi. However, they’ve also been finding it more often east of the Mississippi, even in Breton Sound.

Freshwater from the rivers forms a layer atop salt water in the Gulf, a process called stratification, and the nutrients in the freshwater feed blooms of algae, and plankton and other critters eat them and die, sinking to the bottom, where they decompose, using up oxygen in the lowest part of the salt water layer. The oxygen levels get very low, below 2 milligrams per liter.

Research indicates the dead zone is linked to increased costs for fishers, who might have to travel farther to catch fish or shrimp escaping the low oxygen.

Our coastal fisheries are a very important part of the state’s economy, the last productive wild coastal fishery outside of Alaska in the lower 48 states, so it’s certainly an issue, a resource and ecosystem that’s of primary importance for Louisiana, its commercial and recreational seafood industries, our restaurant industry, all those basics.

The action plan is designed to reduce the size of the low oxygen area before it grows to the point where a major impact to fisheries could happen. One of the key strategies was not to wait for a major impact to happen.

Map of measured Gulf low-oxygen hypoxia (dead zone), July 23 - July 28, 2023. Red area denotes 2 mg/L of oxygen or lower, the level which is considered hypoxic, at the bottom of the seafloor. (Bottom) Size of the hypoxic zone (green bars) measured during annual summer ship surveys since 1985, including the target reduction goal established by the Mississippi River/Gulf of Mexico Watershed Nutrient Task Force and the 5-year average measured size (black dashed lines). (LUMCON/LSU/NOAA)

The most recent task force report to Congress relies on U.S. Geological Survey data to say that the interim goal of a 20% reduction in nutrients has been met, in advance of the 2025 timeline. Is that accurate?

At the most recent task force meeting, USGS officials gave a slideshow that said if you use a method they call flow normalizing to deal with year to year variations, it looks like they may be close to reaching that 20% goal. But Dr. Gene Turner at LSU has pointed out that they’re using benchmarks that go back before the hypoxia action plan was in effect to determine the 20% reduction, and it might not really be showing that much of a reduction since the action plan began, which is what the goal is supposed to be based on. The key point, though, is that things would be worse if we hadn’t done things during the action plan’s timeframe. But we haven’t really achieved that plan’s reduction goal.

This graphic shows the locations of cities and farms that produce nutrients that enter the Mississippi and Atchafalaya river systems and cause algae blooms in the Gulf of Mexico that result in the creation of low-oxygen hypoxia conditions, the dead zone.

How will the states meet the 2035 final goal of a 48% reduction in nutrients to reduce the size of the dead zone to 1,930 square miles?

There are two basic things you can do. Try to keep the nutrients from getting into the water, and once it’s in the water, try to take it back out. Those involve restoring more watersheds and wetlands all along the Mississippi River Basin, capturing the nutrients and processing them within the ecosystems before they go downstream.

But the issue of scale comes in. How do you increase the scale of these activities on the timeframe needed to reach the goal, which is the critical element? The plan's a cooperative agreement among states. It’s not legally binding, though it represents a commitment by all the parties that they will help.

They missed the first target date for reducing the dead zone (to 1,930 square miles) in 2015, and we now have just another 10 years to reach the revised target date, set in 2015. We had 10 years to reach this interim target date of 20%, and having been a participant in the process, I can state for the record that it was not a priority. It was rarely discussed. There was never a sense of urgency about it.

One exception was that Sen. Bill Cassidy (R-Louisiana) included a provision in the bipartisan infrastructure law that directed funds to the states on the task force to carry out nutrient reduction activities. But the scale was modest, just $60 million over five years.

Unfortunately, there has been no organized effort on the part of the task force or the state of Louisiana to go after those resources.