This is the fourth story in The Guardians, a 6-part series highlighting those dedicated to saving and passing down New Orleans' unique heritage.

Kathe Hambrick was picking up straight pins in her aunt’s hat making room on April 4, 1968, when the TV began blaring news about a shooting in Memphis. Martin Luther King Jr. had been shot.

Just 10 years old, Hambrick didn't fully grasp what had just happened. But she knew it was something big.

“I could feel she was stunned,” Hambrick said, recalling that her aunt's sewing machine went silent. “She didn’t say anything.”

Living in south central Los Angeles in the 1960s, Hambrick had a front-row seat to the major events of the civil rights era. Her uncle was the pastor of a large church that was active in the push for equality. Nat King Cole and Mahalia Jackson went to that church to raise money for the fight. She lived just blocks from the site of the Watts riots.

Hambrick didn’t realize it at the time, but those early experiences ignited her passion to unearth the stories of the thousands of enslaved people who powered the profit-making industries of the Deep South, especially the plantations along River Road between Baton Rouge and New Orleans.

“I try to think back on that and ask myself, has that in any way impacted my interest in preserving this history?”

Executive Director Kathe Hambrick, left, with Lisa Moore, middle, head of research services, and Anna LeBlanc-Mulder, far right, a reference archivist, inside the Amistad Research Center in New Orleans on Monday, November 13, 2023.

More than five decades later, Hambrick serves as the executive director of the Amistad Research Center, the largest independent archive of Black history in the world. It's the culmination of Hambrick’s years of work in preservation and education, which began at the small River Road African American Museum in Donaldsonville she founded and ran for more than two decades. She also served as president of the Association of African American Museums.

The decades Hambrick has devoted to the topic gives her a unique perch from which to act as both preserver and promoter of one of the most important elements of Louisiana history — that of its Black residents.

‘Culture shock’

Hambrick’s formative years may have been among palm trees and beaches, but her connections to south Louisiana were strong.

Kathe Hambrick, founder of the River Road African American Museum and executive director of the Amistad Research Center, gives an oral history in one of the museum buildings in Donaldsonville on Thursday, December 7, 2023. It was formerly the office of Dr. John H. Lowery.

Born in New Orleans in 1958, her father moved the family to California when she was three to get out of the south, Hambrick said. In 1969, the family moved back. But instead of returning to Hambrick's native New Orleans, they moved to Gonzales, where her father took a job in the family funeral home and insurance business.

For Hambrick, Ascension Parish was “culture shock.”

“Why are we coming back here?” she remembers asking. “I don’t have any family here. I don’t want to be here.”

When she graduated from the recently integrated East Ascension High School in the mid-1970s, she only wanted one thing.

“A plane ticket out of here,” she told her parents. “I said ‘I will never live in the rural south again.’”

A twist of fate, and the economy

Hambrick returned to southern California for college, graduating in 1982 with a degree in English and a minor in African American studies. She took a job at IBM, where she stayed for 12 years before being laid off.

Then she did what she swore she would never do. She returned to Ascension Parish.

Once back in Louisiana, Hambrick found herself going through boxes of old obituaries at the family’s funeral home. One stood out: A 92-year-old woman who had been born on a plantation.

“I’m going, ‘That’s right, I’m back in plantation country,” she recalled. The realization kindled her curiosity.

Kathe Hambrick in the archive room of the Amistad Research Center in New Orleans on Monday, November 13, 2023.

Hambrick decided to go on plantation tours which, back then, still cast the era of slavery through a gauzy lens, with hoop-skirted tour guides talking glowingly about the merits of antebellum life.

“I was so disturbed by it,” she said. The tours, she said, didn’t “mention anything about Black people.”

Not only that, those plantations were more about winning tourist dollars than they were about showing what plantation life was really like.

When she asked questions, she found nervous tour guides unable to answer her.

“So I did my own research,” she said. Digging through libraries at Amistad, LSU and Tulane, she found property records that included the names of enslaved people.

But no one was telling those stories.

“It’s bothering me so much that I’m really kind of losing sleep,” Hambrick recalled. During one of those sleepless nights, Hambrick made up her mind: She would create her own museum, one dedicated to African Americans along the river between Baton Rouge and New Orleans.

From idea to existence

On a recent morning, Hambrick stood in an airy classroom in a renovated schoolhouse in Donaldsonville. The school building was dedicated in October and is now one of the River Road African American Museum’s centerpieces, a light and airy space with hardwood floors and displays on the wall.

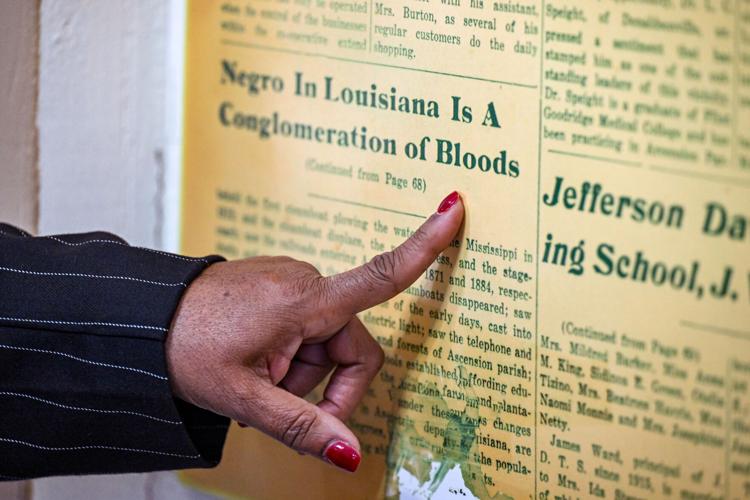

Kathe Hambrick points to a historic news clipping about a doctor who previously worked in Donaldsonville at the River Road African American Museum on Thursday, December 7, 2023.

The building itself is an artifact. It was part of the network of Rosenwald Schools, which were built across the rural south to provide places for Black students to learn. The one Hambrick has rehabbed was originally in St. James Parish. There, the school board offered to sell it to her for $1, with the caveat that she had to move it. Raising the money and actually getting the building across the river to Donaldsonville took several years.

But now it’s ready to welcome visitors.

The building is just the latest example of what her museum has become since it opened in 1994, then on the grounds of Tezcuco Plantation. It has grown by leaps and bounds, and now occupies six sites sprinkled through downtown Donaldsonville.

It wasn’t always easy: Funding was always an issue. Hambrick knew nothing about museums and had to learn. Then she had to convince state officials and the owner of Tezcuco Plantation — a high school acquaintance — to allow her to put the museum on the plantation’s grounds.

Hambrick also had to figure out how she wanted to tell the story of enslaved people and their descendants, a complex and daunting task. Plantation life would be part of the story, but not the whole story, she decided.

“Where are the schoolhouses? Where are the churches? Where are the shotgun houses and the houses where people lived, learned and loved each other beyond the plantation?” she asked. “When I opened the museum, I said, ‘When Black people come to this museum, I don’t want them to leave feeling like victims.’”

More than preservation

Kathe Hambrick, founder of the River Road African American Museum and executive director of the Amistad Research Center, fist bumps her brother, Darryl, inside of one of the museum buildings in Donaldsonville on Thursday, December 7, 2023.

Over the years, Hambrick, along with her brother Darryl, served in whatever role was needed at the time: collector, curator, grant writer, tour guide. They even shepherded the museum through a catastrophic fire that burned Tezcuco in 2002 and forced both the plantation to close and left the museum without a home. Eventually, they found space in downtown Donaldsonville.

Through it all, preservation has been a key part of the mission.

A few blocks from the Rosenwald schoolhouse, Hambrick unlocks the door of a small shotgun house. The house once served as the office of Dr. John Lowery, one of the first Black doctors in Donaldsonville. Pointing to an old cabinet, Hambrick notes that the museum kept some of Lowery's instruments, vestiges of his post-Civil War practice. Lowery, who died in 1941, was not just a doctor, but a planter and a key supporter of education in Ascension Parish.

From L-R: Roy Quezaire Sr.; Ernest Claverie; Lyman White; Kathe Hambrick, director of the River Road African American Museum; John Francis Sr.; Prince Davis Sr.; Donaldsonville Mayor Ray Jacobs; and Ulysses Landry. The group stands in front of Friendship Hall in Donaldsonville, La. in February 2001.

For Hambrick, it's not just about artifacts. It's about stories.

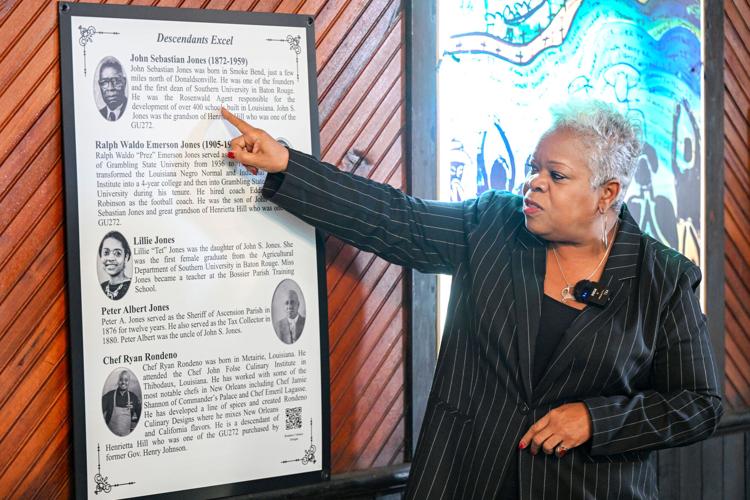

Down the street from the Lowery house is a decommissioned church building. When the museum obtained the building, Hambrick got new decorative windows made for the church. The window images now highlight the lives of enslaved people on the sugar plantations, especially the members of what is known as the Georgetown University 272, a group of enslaved people sold by the university to plantation owners in south Louisiana in 1838. There are QR codes that, when scanned, will pull up the original documents that detail the sale, Hambrick noted.

Hambrick's drive to tell these stories has been instrumental in the museum's growth, said Darryl Gissel, a businessman and former Baton Rouge mayoral candidate who has served on the museum’s board.

“Kathe tells the story in a very profound way," Gissel said. “What Kathe created, it has a big impact."

Kathe Hambrick, curator of the River Road African American Museum at Tezcuco Plantation, sits in the museum with various artifacts from the slavery era on display in February 2000.

Her passion has never been more important than in tough times, like the Tezcuco fire or during COVID.

“The struggle was huge,” Gissel said. “It’s a passion of hers.”

The Amistad

Now Hambrick has taken that passion to the Amistad’s collection, with more than 15 million documents, 250,000 photographs and 30,000 books. Founded in 1966, the center moved to New Orleans in 1970, first to Dillard University, then to a site in the French Quarter and eventually to its current home on Tulane's campus. It houses collections of several authors of color, as well as archives of government reports on civil rights and other topics, periodicals, graphic novels and fine art. The center's annual budget is about $1.3 million.

Kathe Hambrick, bottom center, in the multi-level archive room of the Amistad Research Center in New Orleans on Monday, November 13, 2023.

Hambrick brings unique skills to the table, said Kim Boyle, a New Orleans-based attorney who chairs the Amistad board.

“Every time I am around Kathe, I witness her strengths on display,” Boyle said. “Kathe is the right person at the right time.”

Board members hope Hambrick can grow the center’s profile, budget and research footprint, Boyle said, the same way she built the River Road African American Museum from nothing to what it is today. While the Amistad is a major research resource, it is not as well known as it should be.

“Our importance has not always been recognized,” Boyle said. Hambrick’s mission is to “Take what’s already there and bring it forward and develop it."

The Amistad should have global reach, Hambrick said.

The center should be "recognized as the largest repository of history for marginalized communities in the world," she said. "I want to share its importance with the world."

Editor's note: A photo caption has been corrected to properly identify Lisa Moore and Anna Leblanc-Mulder.