Louisiana often struggles when it comes to acknowledging what's fair and just.

For example, our state has seven state Supreme Court justices, only one of whom is Black. It's been that way for a number of years now, but it didn't happen without a fight.

For generations, majority-Black Orleans Parish was combined with majority-White St. Bernard, Jefferson and Plaquemines parishes, diluting Black voter strength. That finally changed 32 years ago.

A lawsuit filed in 1986 alleged that the all-White Supreme Court would never be more diverse without redrawing the court's district maps to give Black voters a chance to elect someone of their choosing.

The plaintiffs — Ronald Chisom, Marie Bookman, Walter Willard, Marc Morial, Henry Dillon, III and the Louisiana Voter Registration/Education Crusade — ultimately prevailed in 1991. A year later, a federal consent decree created a majority-Black district in Orleans Parish.

Black Louisianans finally had a seat — known to many as "the Chisom seat," tied to the case name — and a voice on the state's highest court.

Civil District Court Judge Revius Ortique Jr. won that seat in 1992, becoming Louisiana's first Black associate justice. He retired in 1994.

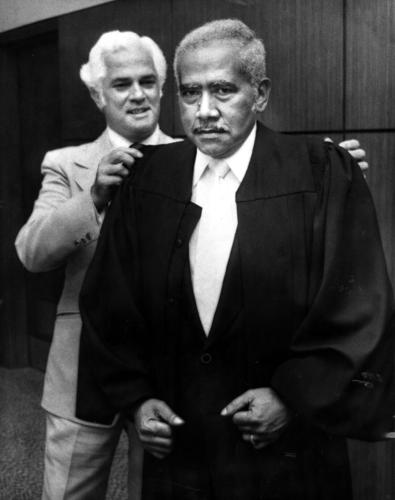

State Supereme Court Justice Pascal F. Calogero, background, helps Justice Revius Ortique Jr. into his robe after swearing-in ceremonies in 1978. Ortique was the first Black Louisiana Supreme Court justice when he was elected to the bench in 1992. He retired in 1994.

Ortique was succeeded by Justice Bernette Joshua Johnson, who served on the court from 1994-2020 — retiring as Louisiana's first Black Chief Justice.

Associate Justice Piper Griffin now holds that historic seat.

Louisiana Supreme Court Chief Justice Bernette Johnson, retired in 2020 after 26 years on the bench. She was the second Black justice on the court. She was Louisiana's first African-American chief justice, serving in that role from 2013 until her retirement. (photo courtesy Louisiana Supreme Court)

Johnson had a distinguished career as an attorney and jurist who championed issues of importance to Black individuals and communities, and others. She worked tirelessly to infuse the legal profession with diversity and inclusion in pursuit of fairness, equity and justice.

While in law school at LSU, Johnson worked on civil rights cases with veteran attorneys. After graduating, she worked as the managing attorney for the New Orleans Legal Assistance Corporation, or NOLAC, an agency that represented people who could not afford to hire lawyers.

Her work at NOLAC included matters involving disenfranchised people, elderly people, young people who found themselves in the juvenile justice system, and children with legal issues. She promoted using Limited English Proficiency interpreters to make ethnic and racial fairness a "best practice" in courtrooms.

Those things made a big difference to disenfranchised communities.

Former Orleans Parish Civil District Court Judge Piper Griffin won election to the "Chisom seat" on the Louisiana Supreme Court as an associate justice, succeeding retiring Chief Justice Bernette Johnson, who was on the bench for 26 years.

Now, those gains are under attack.

Attorney General and Gov.-elect Jeff Landry, with his appointed solicitor general, Liz Murrill, who is running to replace Landry, went to federal court seeking to eliminate the Chisom consent decree. A district court judge rejected their arguments.

Landry appealed to the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. A three-judge panel ruled 2-1 against Landry on Oct. 25, agreeing with the trial court that Landry failed to give a good reason to dissolve the decree. Landry now must decide whether he will ask the full Fifth Circuit to consider the matter.

Tyronne Walker, the Urban League of Louisiana's vice president for policy, strategic partnerships and development, said if Landry "doubles down" with an appeal it would be a clear message that he wants to strip Black voters of the opportunity to choose representation on the state's highest court.

"They're saying 'Trust us to do the right thing going forward,'" Johnson, now 80, said in a Thursday interview. I have to say I agree with the former Chief Justice. I, too, don't find current politicians to be that trustworthy. I want federal protection.

If Landry truly wants to be the governor of all Louisianans, he should let this go and concentrate on a strong transition as he ramps up to replace Gov. John Bel Edwards.

I'm confident that Black voters will give him credit for doing the right thing if he recognizes the importance of the Supreme Court's "Chisom seat" and allows Black Louisianans to elect successors to Ortique, Johnson and Griffin in the future.

The truth is, with a Black population of about 33%, Louisiana should have TWO Black Supreme Court justices.

Johnson said some Black people don't seem to understand how important representation is at all levels of government, including the judiciary. "They don't see the regression," she said. That includes having African-American representation on the state Supreme Court.

I asked Leah Aden, senior counsel for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and lead attorney opposing Landry's suit, what's next.

"Going forward," she said, "the legislature continues to have the authority to rebalance the populations of the Supreme Court districts or even redraw its lines, including to ensure against nondilution in other parts of the state like around Baton Rouge, so long as they do not dilute the Orleans-based district consistent with the consent decree."

Imagine that.