Nearly 20,000 school-age children in Louisiana have fallen off the education map, kids who should be in class but are missing from school rosters, a new analysis of enrollment trends during the pandemic found.

“There’s no doubt that we have issues with chronic absenteeism,” acknowledged State Education Superintendent Cade Brumley. “I would not say it’s worse (here) than in other places, but it definitely needs our attention.”

The analysis, released Thursday, is a collaboration between The Associated Press, Stanford University’s Big Local News project and Stanford education professor Thomas Dee. They found an estimated 240,000 students in 21 states whose absence from school could not be explained, which they said almost certainly understates the real number of missing kids.

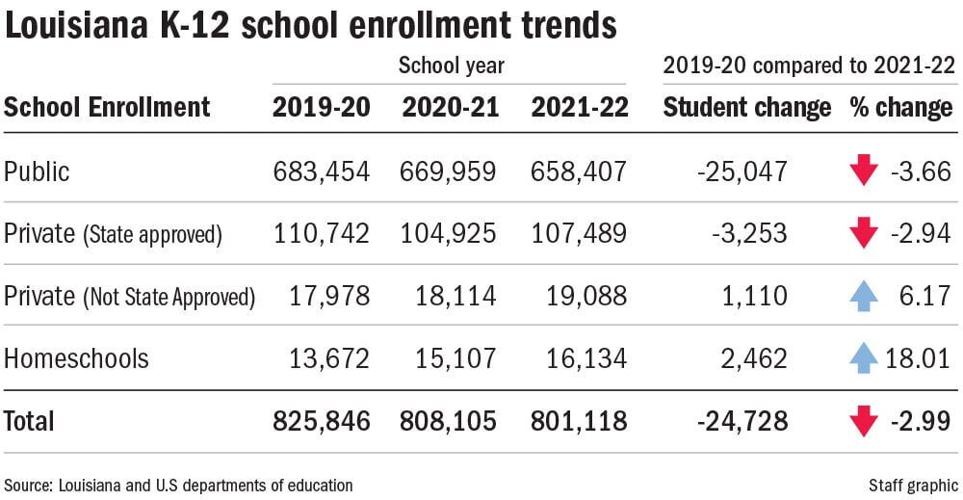

The researchers and journalists gathered enrollment data for the 2019-20 school year, the year before the coronavirus pandemic, and compared it to data from 2020-21 and 2021-22 school years. They compared that data — from public, private and homeschools — against U.S. Census estimates of the school-age population, children ages 5 to 17 years old.

Louisiana was one of 21 states where AP and Stanford amassed sufficient data. Its 19,000-plus missing kids represent 2.4% of the state’s school-age population of nearly 800,000 children, the highest percentage among the 21 states measured.

A state task force began meeting last summer to look at ways to improve school attendance. Brumley said that the data schools collect on attendance needs improving and that there needs to be a better flow of information to local district attorneys charged with enforcing truancy laws.

In addition to the impact of the pandemic, Brumley said major hurricanes in 2020 and 2021 kept many kids out of school for extended periods of time.

“My greatest concern surrounds our third and fourth graders,” he said. “I feel they have been the most-storm impacted children, and school systems need to act with urgency and be assertive to make sure they will work with those kids.”

Declining enrollment

Between 2019 and 2021, public schools in Louisiana lost nearly 25,000 children, a 3.6% decline. Those declines continued in 2022, according to the most recent data.

Private schools in Louisiana also had about 3,000 fewer children enrolled in fall 2021 than they did two years earlier. That’s a contrast with the other 20 states, where growth in private school enrollment explained 14% of the kids no longer in public school.

Louisiana has not yet released private school data for the current school year, so it’s unclear if their enrollment is still down.

Pattie Davis, superintendent of Catholic schools for the Diocese of Baton Rouge, said the current data shows overall enrollment in the diocese’s 30-plus schools is up slightly from where it was pre-pandemic.

“We’re moving in the right direction and learning what is actually working for students,” said Davis, who took over as diocesan superintendent in spring 2022.

Of the 28,300 fewer children in public and private schools in fall 2021, almost 20% can be explained by a 5,500 student decline in Louisiana’s school-age population over the course of the pandemic, according to Census. The decline is a mix of lower birth rates as well as children moving to other states.

After concerns were raised about the reliability of Census estimates, AP and Stanford looked at enrollment trends in two states prior to the pandemic. That analysis found almost no missing students at all, suggesting the high numbers of unaccounted-for children during the pandemic were unusual.

Homeschooling up

Another factor was homeschools. About 12% of the kids who left public and private schools — about 3,500 children — ended up enrolling in homeschools or small private schools that register with the Louisiana Department of Education but have no plans to try to comply with state rules that apply to traditional private schools.

Erin Bendily, vice president for policy & strategy for the Pelican Institute in New Orleans, tracks homeschools closely. While the homeschool sector had already been growing steadily, the pandemic has accelerated that growth, she said. The rise in parents working from home has allowed parents to take more control over their children’s education.

“Those who have the opportunity to avail themselves, increasingly are doing so,” Bendily said.

Support for homeschooling has also grown dramatically. In the fall, the Pelican Institute released a report detailing some of those support structures after gathering suggestions from members of the homeschool community.

“I was blown away by all of the resources they were pointing us to, not just curriculum,” Bendily said. “There are all these networks where kids are connected with each other across the nation, not just in their neighborhood.”

Missing kids

The biggest part of the puzzle, though, appears to be children not in school at all.

Roxson Welch, executive director of the Family and Youth Services Center, a Baton Rouge-based interagency center created a decade ago to combat truancy, has been sounding the alarm for years about children in town missing school. She says the pandemic has made the problem far worse.

She said many kids were not attending online classes, sometimes without their parent’s knowledge, and have not been back in school since. She estimates that the furthest-behind kids are three to four years behind their peers academically. She said the children who come into her shop are ones with whom some adult noticed something amiss.

“We’ll get a call from a neighbor who says, “those kids, they aren’t going to school, they are wearing their pajamas all day long,” Welch said.

Welch, however, worries that the rest of the education world does not share her urgency, noting that fewer kids are being referred to her agency for help this year than last year. A former classroom teacher, Welch said instructional practices need to adapt to educate these lost children now or they will act out in the future.

“(The pandemic) changed our entire world, but it didn’t change our education system,” she said.