“Tell It Like It Is” was the obvious choice for the title of Aaron Neville’s autobiography.

But “Tell It Like It Was” would have been more accurate.

The Aaron Neville most fans know today is a spiritual, soft-spoken, 82-year-old gentle giant with a heart of gold and an otherworldly voice living a quiet retirement on an upstate New York farm.

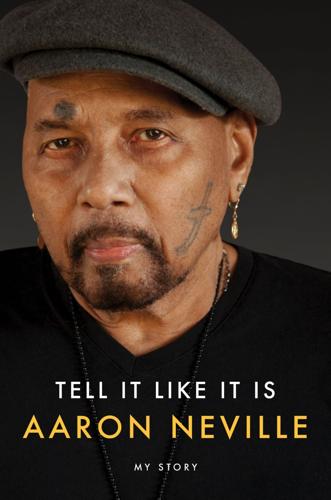

The cover of New Orleans singer Aaron Neville's 2023 autobiography "Tell It Like It Is."

But the character he self-describes across the book’s 271 pages is someone else entirely.

“When I wasn’t singing,” he writes, “I was an angry, drugged-out thug with a voice like an angel but no reason to be one.”

“Tell It Like It Is” (Hachette Books) delves into excruciating detail about his drugged-out thug life. In plainspoken language that sounds like how he speaks, Neville flips through the back pages of his personal story, long before the world tours, Grammy Awards and million-selling albums.

He previously shared some of those details in “The Brothers,” the 2000 oral history he and his fellow Neville Brothers — Art, Charles and Cyril — wrote with veteran scribe David Ritz. Aaron’s new memoir takes readers along as he injects heroin with strangers in urine-soaked New York “shooting galleries” and with Ray Charles in a nice New York hotel room. He recounts, with a junkie’s eye, the bloom of blood in a syringe and the craving for the high that followed.

“I smoked, swallowed, snorted and injected a large variety of dope for a big part of my life,” he admits, “and I’ve done a lot of stupid things, crazy things, desperate things to feed that habit.”

His life’s other compulsion, music, was the source of his solace and eventual salvation. Concluding Neville Brothers concerts with “Amazing Grace” was as meaningful for him as it was for fans.

“When I had the audience hypnotized with the swirling notes that God let me be able to do, it was a kind of sacrament. The notes I had in my soul, whenever I was singing each one, would go through my veins like some precious lava. No matter what I was singing, I could feel God in each note coming out of me.”

Growing up with the good and bad

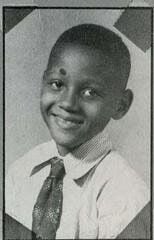

He describes a relatively idyllic New Orleans childhood with a loving mother and a no-nonsense father. He landed his first professional gig around age 11, singing with eldest brother Art’s doo-wop group.

New Orleans singer Aaron Neville as a little boy.

Aaron likens his own vocal approach to “connecting the dots, going from one octave to another.” He modeled it on the yodeling style of Roy Rogers, Gene Autry and other “singing cowboys” he loved as a boy. Later, he considered Sam Cooke to be “like a god."

He and his teenage pals Melvin and Marvin found trouble early. Neville recalls singing songs by the Drifters and Sam Cooke with Marvin and Melvin as they looked for cars to steal.

His 16th birthday present to himself was a crude tattoo dagger on his left cheek, administered at home by a friend with two needles tied to a matchstick: “I guess stupid was set in place at that age.”

So many stupid moments could have turned out much worse. After being sucker-punched in the mouth, Neville pulled out a borrowed pistol, shot his assailant twice, then fled. Not until years later, when he encountered and befriended the man in prison, did he know if he’d lived or died.

He met his future wife, Joel Roux, when they were still teenagers and was smitten immediately. Her parents were wary of him even without knowing he was picking her up for dates in stolen cars.

When Joel got pregnant, Neville dropped out of school in 11th grade and got married two weeks shy of his 18th birthday. Street smarts, not school smarts, would have to suffice.

Two months after their first son, Aaron Jr., was born, Aaron Sr. received a six-month jail sentence. Ashamed, Joel changed their son’s name to Ivan (the name Aaron Jr. stuck when it was later applied to the couple’s second son).

Angry about the name change, Aaron got a “Teresa" jailhouse tattoo on his chest — "Teresa" being the name of a drug dealer’s girlfriend who supplied him with dope in prison.

His frustration also inspired him to write “Every Day,” which, after his release in 1960, became the first song he recorded. He toured with bandleader Larry Williams in a nonstop carnival of chaos.

Busted in L.A.

Williams lured him to Los Angeles with the promise of work. The “work” involved joining a burglary crew. Soon busted, Neville was sentenced to a year of community service, which he served in 1963 fighting forest fires near Pasadena, Calif.

Back in New Orleans, he recorded “Tell It Like It Is.” The single raced up the charts in 1966 and Neville hit the road. One night in Tampa, Florida, Jimi Hendrix sat in.

Aaron Neville performs on the Gentilly Stage at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival on Friday, May 4, 2018.

The song’s success didn’t turn into a career. Neville was soon back in New Orleans hustling work on the docks and performing with Art Neville & the Neville Sounds and alongside Cyril and organist Sam Henry in Sam & the Soul Machine.

Danger and drugs were constants. The owner of the Greystone, a West Bank club, sometimes paid Aaron in heroin, he writes. Outside the Desert Sand at Claiborne and Esplanade, Cyril got sliced in a fight. At the hospital, doctors sewed up his neck with more than 100 stitches. Cyril then returned to the Desert Sand and finished the gig.

Near-constant harassment by police compounded Aaron’s sense of hopelessness. He lost track of how many times he was picked up and held for 72 hours without charges.

Seeing no path forward, his drug use accelerated. After Joel and the kids left to live with her parents, her man-child husband and Cyril retreated to New York to stay with Charles.

All three were on heroin. In an apt metaphor for his life at the time, he nodded out on the subway, missed his stop and lost the box of family photos he carried with him.

The Neville Brothers are born

Back in New Orleans, he and his three brothers backed their uncle, Big Chief George “Jolly” Landry, on “The Wild Tchoupitoulas” album. That was the genesis of the Neville Brothers. By the early 1980s, they were sweating through long, legendary nights at Tipitina’s. World tours followed.

The book moves quickly, often skimming the surface instead of delving deeply. He does make a point of describing his relationship with Linda Ronstadt, a collaboration that finally elevated him to a higher tax bracket, as strictly platonic.

Aaron Neville, right, joined Trombone Shorty and Orleans Avenue to close out the Acura Stage at the end of the 50th New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival in 2019.

He returned to rehab in the early 2000s, between recording two gospel albums, to break a dependency on pills. He relapsed again, the book reveals, after Joel’s death from cancer in January 2007, as he numbed his deep sorrow with her leftover pain meds.

It wasn’t until he met Sarah Friedman, the photographer People magazine assigned to shoot the Neville Brothers in 2008, that he finally escaped substance abuse for good. He wanted her more than the drugs.

His love for, and devotion to, Friedman — one of his three “earth angels,” following his mother and Joel — sings out from the pages. It was Friedman, he writes, who discovered that the woman who’d been his and the Neville Brothers’ business manager for many years had siphoned vast sums from his accounts.

Some New Orleans details in the book are off. Charity Hospital is identified multiple times as “the charity hospital.” Galvez Street is misspelled “Galves.” Mardi Gras, or Black Masking, Indians are referred to as “krewes” instead of the more commonly used “tribes.” And the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival started in 1970, not 1976.

But overall, the book lets Neville, in his own words, tell it like it is. Or like it was. “When I was onstage, I was closest to my true self, closest to God,” he recalls. “My heart was turned inside out so everyone could hear what was in it.”

"Tell It Like It Is" is equally revealing.

Correction: An earlier version of this aticle misstated the year People magazine sent Sarah Friedman to photograph the Neville Brothers. It was in 2008.