The 2023 Atlantic hurricane season ended last week as one of the most active seasons in the last 70 years. Yet here in Louisiana, where not even a tropical storm made landfall, it felt like a quiet year.

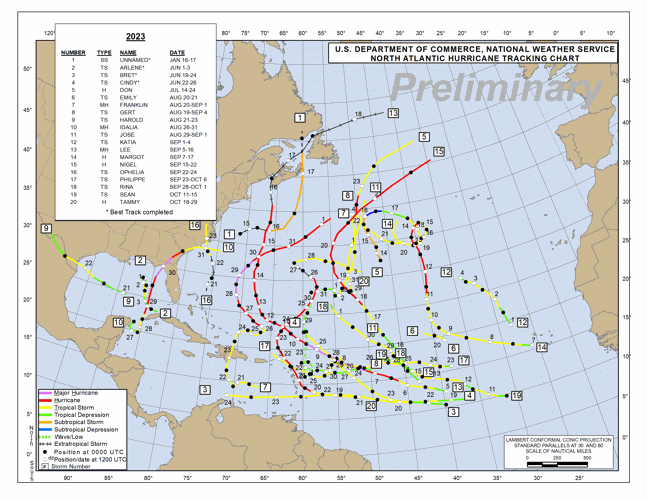

Of the 20 named storms that formed in the Atlantic Ocean, just three made it to the U.S., including Hurricane Idalia, which hit Florida's Big Bend region in August as a Category 3 storm, causing extensive damage and killing five people. Tropical storms Harold and Ophelia hit Texas and North Carolina, respectively.

But a majority of the year's storms meandered out at sea for days and sometimes even weeks, in many cases turning sharply northeast after heading west across the Atlantic in the general direction of the U.S.

That's largely thanks to El Niño. Here's how the climate pattern impacted New Orleans and this year's storm season:

What is El Niño?

El Niño and La Niña are two opposing climate patterns that disrupt normal wind and current conditions in the Pacific Ocean, in turn impacting weather patterns across the globe. El Niño and La Niña events can last for between 9 months or several years, according to the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration. They generally occur every two to seven years, but they don’t occur on a regular schedule.

During El Niño, trade winds that normally blow west along the equator weaken. This pushes warm water that would normally move toward Asia back east, where it settles along the west coast of the Americas.

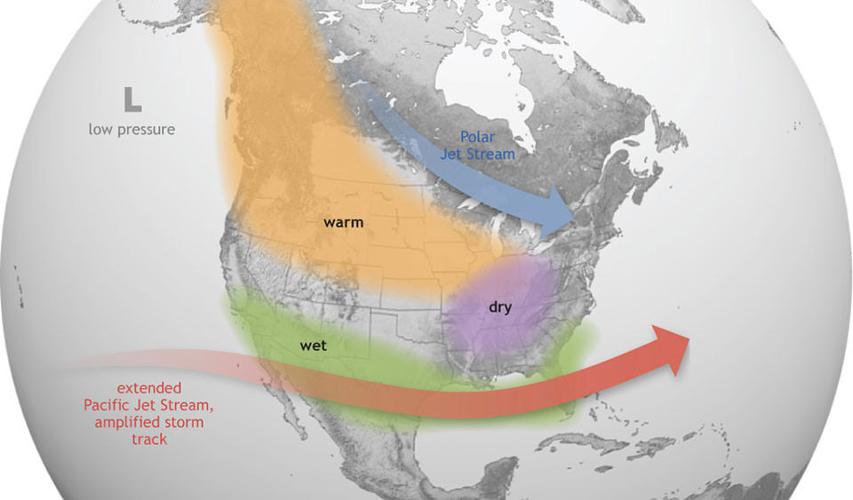

These warmer waters cause the Pacific jet stream, a narrow but fast moving current of air, to intensify and move south of its usual position. That blows win shear over the Atlantic, making it harder for tropical storms and hurricanes to form and bringing wetter conditions along the U.S. Gulf Coast and southeast.

El Niño causes the Pacific jet stream to move south and spread further east. During winter, this leads to wetter than normal conditions in the South and prevents some tropical storms from reaching the U.S.

In short, El Niño is typically associated with fewer Atlantic storms and higher rainfall totals along the Gulf Coast.

El Niño's impacts this year

Hurricane forecasters weren't sure how the 2023 hurricane season would turn out, according to David Roth, a meteorologist at the National Weather Service Weather Prediction Center.

While an El Niño year would typically mean fewer storms in the Atlantic, sea temperatures this summer were unusually high, which Roth said conversely makes it easier for storms to form and build strength.

"This is probably one of the most active seasons we've had during El Niño," Roth said.

Another lead hurricane forecaster with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Matthew Rosencrans, agreed, saying in a previous interview that "record-warm ocean temperatures in the Atlantic provided a strong counterbalance to the traditional El Niño impacts.”

This map shows the track of every named storm that formed in the Atlantic Ocean in 2023.

While an average Atlantic hurricane season gets 14 named storms, including seven hurricanes and three major hurricanes, 2023 saw 20 named storms, seven of which were hurricanes and three that were major hurricanes.

And despite El Niño's usual effects on the Gulf Coast, this year also proved to be an abnormally dry one in New Orleans, where Roth said average rainfall totals are behind by nearly 2 feet. It could still rain more later this month, he said, but only so much.

Still, Roth said the presence of one hallmark El Niño characteristic was certainly felt this year — its wind shears. Those shears, which generally blow east-northeast across the southern coast of the United States, weakened a number of storms and caused others that were headed generally toward the U.S. to veer back out to sea.

Without those winds, Roth said it's likely Hurricane Idalia would have landed in Louisiana or Texas, rather than turning northeast toward Big Bend.

The "heat dome"

This summer's record-breaking heat, in a way, also helped to ward off some of this year's storms.

Though long-lasting high temperatures can create conditions conducive to hurricanes, Roth said this summer's high temperatures came with what one might describe as a dome of high pressure that blanketed a large portion of the U.S. That made it harder for thunderstorms to form along Louisiana's coast, and forced at least one storm, Harold, to go around us, making landfall near the Texas-Mexico border instead.

The 2024 hurricane season

It's not clear yet whether El Niño conditions will stick around for another year, Roth said, but that will obviously play a role in how active next year's hurricane season is. Colorado State University is expected to put out its forecast sometime next spring.

Until then, Roth said "nobody knows" what the 2024 season might bring.