Ashton Galbo couldn’t believe she was pregnant at 17.

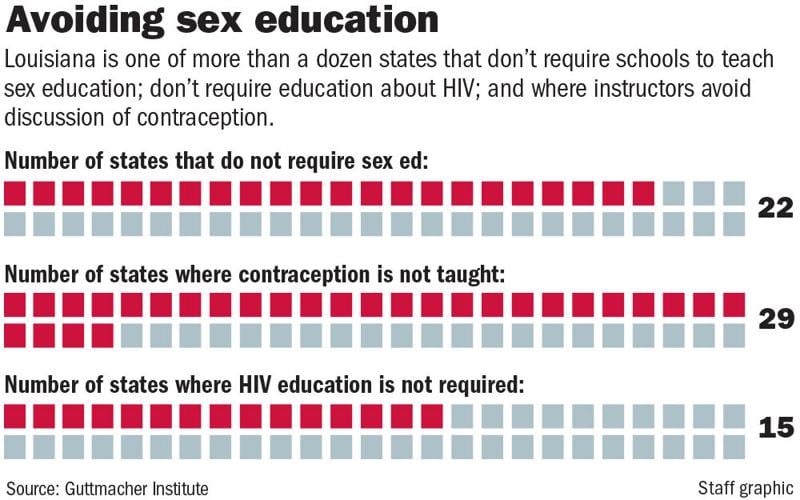

She had taken a basic health class at her suburban Louisiana high school, but she never learned about options for preventing pregnancy or where to go for help. Then, as now, schools in Louisiana — unlike in most of the rest of the country — are not required to teach sex education.

She felt sick, physically and emotionally. She tried to hide her pregnancy from her mom. Her nausea was so severe she had to be hospitalized and carry an IV pump with medicine.

“It was very scary, very overwhelming,” said Galbo, now 25.

More teen pregnancies, more infant deaths: Louisiana teenagers are more likely to give birth than those in most other states, while schools aren’t required to teach sex ed.

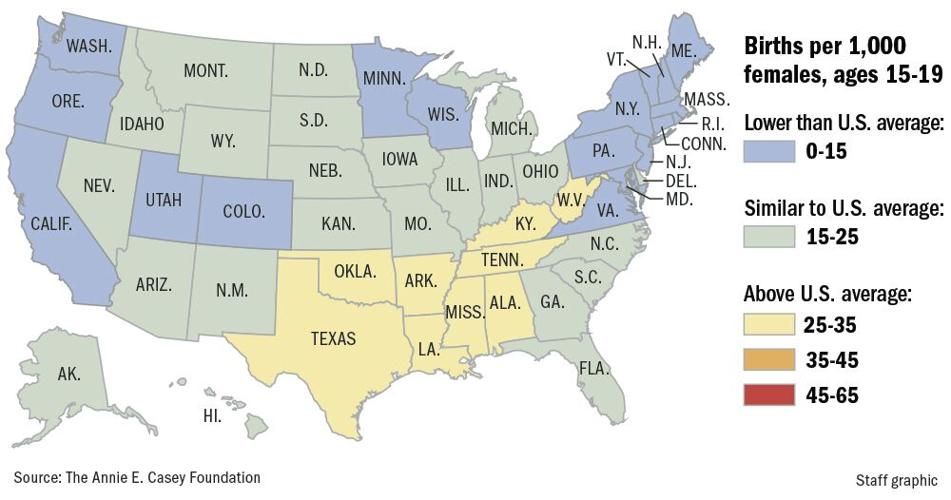

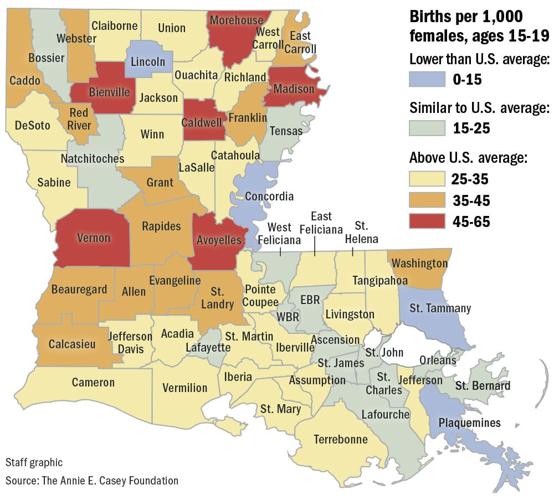

Her plight is common in Louisiana. The state’s teen birthrate is double the national average — and it’s one of the causes underlying Louisiana’s infant mortality crisis. Babies die here at some of the highest rates in the developed world.

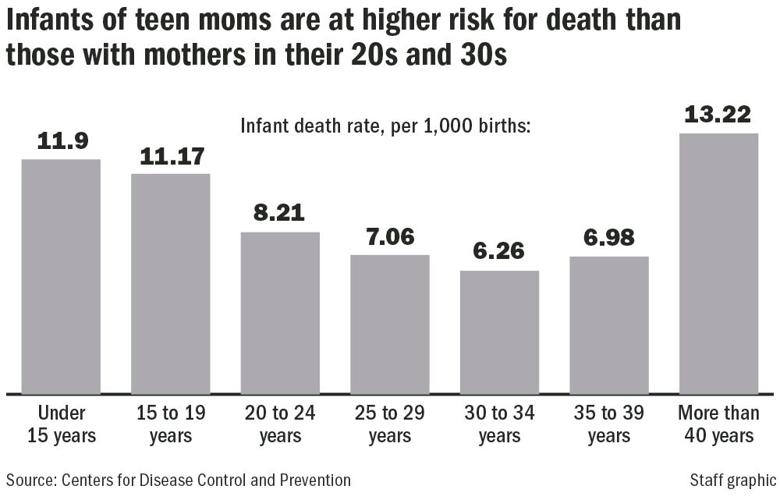

And babies of teens are among the most at risk. Babies born to mothers between ages 15 to 19 are nearly twice as likely to die in their first year of life as those born to mothers between 30 and 34, according to national data. Infants whose mothers are under 15 have even worse outcomes.

Teenagers’ bodies are smaller and their hips are narrower than women in their 20s and 30s. Physicians say that may make teens less prepared physiologically to give birth, leading to more preterm births, low birth weights and complications during delivery. And many teenagers go without prenatal care because they are too scared to tell anyone they are pregnant.

“Oftentimes, they won’t come in for their first prenatal visit until they’re 20, 21 weeks because they thought they could hide it until they start showing,” said Dr. Ronak Shah, an obstetrician for Our Lady of the Angels in Bogalusa. “So that sometimes brings up some complications.”

Shah said young, first-time pregnant Black women are often at higher risk for the blood pressure condition preeclampsia or eclampsia.

That was the case for Ke’Shawn Harris, who got pregnant when she was 16 in Westwego. She developed such severe preeclampsia that she had to deliver her son six weeks early.

Her son, Ja’Quan, didn’t need long in the neonatal intensive care unit before they sent him home, but he had seizures for his first few years of life. He eventually grew out of them, while Harris went on to get two degrees in 2010 and 2016 and had three more children.

Ke'Shawn Harris was 16 when she got pregnant in Westwego. She had preeclampsia and had to be induced six weeks early.

Her first was 23 years ago.

A decade and a half passed between Harris and Galbo’s pregnancies. But the state’s approach to sex education hardly changed over that time.

“Sex ed isn’t even a thing,” said Grace McKendall-Thompson, now 26, who got pregnant her senior year of high school in New Orleans. McKendall-Thompson said she was throwing up in her high school bathroom between classes and setting off rumors at prom that she might be pregnant.

She had her first baby, Hassan Jr., shortly after she graduated in 2015 and later married his father and her high school sweetheart. They now have three sons together, and she’s working on her bachelor’s degree with help from a new program called Generation Hope that helps teen parents in New Orleans.

She’s gotten free counseling, tuition support, activities for her kids and mentorship through the program. McKendall-Thompson said she was especially grateful to be paired with a mentor who also has an autistic child. Two of her three boys have been diagnosed with autism.

Grace McKendall-Thompson, right, with her husband, Hassan Thompson Sr., and sons, Huey, 4, in her lap, Hassan Jr., 8, left, and Hosea, 5, at their home in New Orleans East, photographed Friday, Dec. 1, 2023. (Photo by Scott Threlkeld, The Times-Picayune)

But too many teen moms go without those sorts of resources.

Galbo’s baby, Harper-Layne, was born in 2016 in Baton Rouge. She was among 4,500 babies born to teens in Louisiana that year.

Galbo thought about putting Harper-Layne up for adoption before she felt confident that she had enough support from her family to raise her.

“Girls need to be supported, they need to be told there’s help out there and not being made to feel ashamed or embarrassed or alone,” she said. “Knowledge is power. Knowing what your options are, knowing your body, where you can go for help — it will make all the difference in the world.”

Harper-Layne, 7, plays piano in her home on Thursday, November 30, 2023.

Galbo later got an associate degree. She now works for the East Baton Rouge Clerk of Court’s Office and is married and pregnant with her second child.

Louisiana still doesn’t require schools to teach any form of sex ed, let alone anything about contraception, though the state ranks among the top five in the nation for rates of sexually transmitted diseases. Those can also be deadly for babies: cases of congenital syphilis among infants have soared since the pandemic and greatly increase risks of stillbirth and infant death.

While Louisiana law allows individual schools to teach sex education starting in seventh grade if they choose, none must teach it. Orleans Parish schools may teach sex ed starting in third grade.

“It’s not our children’s fault when they end up in these situations because we have no standardized sex education in our state,” said Jamilla Webb, a New Orleans nurse who runs an organization called Her Health Nurse to teach classes on sex education, hygiene and more.

More teen pregnancies, more infant deaths: Louisiana teenagers are more likely to give birth than those in most other states, while schools aren’t required to teach sex ed.

State law says sex ed in schools must emphasize abstinence as a means to avoid pregnancy, and no contraceptives may be distributed.

“It’s really a huge problem,” said Dr. Patricia Kissinger, an infectious disease epidemiologist at Tulane. “Maternal mortality, infant mortality, sexually transmitted infections, HIV: these are big issues for young people. And we have neglected our youth in this.”

Even after giving birth, contraception can remain a mystery

A 14-year-old was in labor, and Webb tried to give her a crash course on sex education. She was the youngest patient Webb had ever worked with as a labor and delivery nurse in New Orleans.

“She was crying, she was scared, and she had all these questions,” Webb said. “I asked her, ‘Do you understand how you got pregnant? How your period works? What to expect in labor and postpartum?’”

The girl knew little about what was ahead and was worried about whether she’d get relief from the pain of her contractions. She asked Webb if she could get pregnant from the “pullout” method — which she and her partner had relied upon — and Webb explained to her that she could. Webb, who said she sees herself as a maternal figure to most of her young patients, spent most of her shift with the girl.

Diana Harris unravels a pink decoration at the OMG Girlz clubhouse on Tuesday, November 28, 2023.

Talking about such concepts can be fraught.

Demetrice Smith, a certified nurse midwife and family nurse practitioner, has spent years teaching reproductive health. She has worked with teenagers in New Orleans public schools who were already pregnant or parenting, explaining how their bodies would change during pregnancy, what to expect during birth and how to take care of a newborn.

But the topic of contraception was still off-limits in some cases.

“I had to get specific per parental permission to speak about contraception,” Smith said. “I'm like, ‘Do you realize you have me teaching a prenatal and parenting class in the school?’ That kind of goes without saying we would talk about, how do we not get pregnant again if we're not trying to.”

When she did have permission to teach contraception, Smith said most students had never heard of options beyond condoms.

An expectant mother holds onto an ultrasound photo of her baby while lying on a table at St. Francis Medical Center.

That was the case for Toni Williams, who first got pregnant when she was 13 and living in Jena. Williams got pregnant a second time at 14 and a third at 19. Even after delivering her first baby, Williams said, she did not learn about how to prevent future pregnancies.

In 1990, she was so embarrassed at being pregnant a second time at 14 that she did not seek prenatal care. She went into labor and hemorrhaged at 7 months; both she and her baby nearly died.

Her daughter was transferred to a neonatal intensive care in New Orleans, but Williams was hours away, without transportation. When she eventually got to see her baby — and saw the level of care needed to keep her alive — Williams said she knew she was not capable of providing it. She allowed another couple to adopt her second daughter.

Now 48, Williams eventually got her GED and went back to school to become a certified nursing assistant. She got married and had three more children. She credits good social workers with helping her make it through the difficult times.

Teen pregnancies often remain hidden

It’s common for teenagers to try to hide their pregnancies, sometimes even up until they give birth.

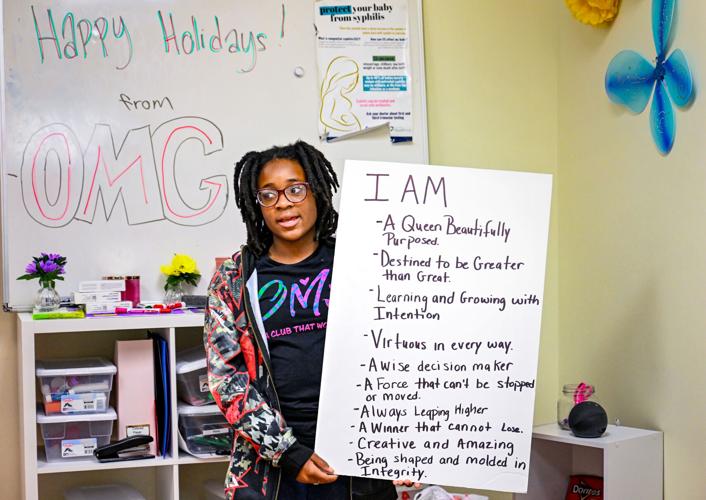

Karleigh Keller leads the OMG Girlz in the affirmation pledge at the start of their meeting at the OMG Girlz clubhouse on Tuesday, November 28, 2023.

Smith remembered helping a teenager through labor during her time as a labor and delivery nurse about a decade ago. The girl had not told her parents she was pregnant, and after having her baby in the afternoon, she said she needed to go home because her mom was expecting her back from school.

Smith coaxed the girl into calling her mom, whom she remembered being understanding and forgiving, given the circumstances.

“Even though they're hard and uncomfortable conversations, these conversations need to happen,” Smith said. “We want our kids to come and speak to us and we want them to know the right information.”

OMG Girlz founder Sashika Baunchand, left, laughs with her Girlz during a meeting where they make arts and crafts for an upcoming parade at the OMG Girlz clubhouse on Tuesday, November 28, 2023.

Helping teens and parents navigate those difficult conversations is part of Sashika Baunchand’s mission with Outstanding Mature Girlz, which teaches girls about leadership, STD awareness and more. OMG Girlz has chapters across south Louisiana where girls attend weekly meetings.

Baunchand said she sees her work as a chance to help parents and supplement whatever girls are learning at home. In some cases, she said parents will even pull her aside and ask her to cover difficult topics that they may struggle to talk about themselves.

“We hear the cliché; learning is supposed to be fun,” said Jessica Cain, one of OMG’s board members. “But it actually is, with the girls being able to take the lead in what they're doing.”

Louisiana an outlier without sex ed, teen surveys

Efforts to change Louisiana’s approach to sex education have repeatedly failed in the Legislature, and the body has only grown more conservative since the latest attempt in 2018.

But even some conservative states have been trying to beef up sex ed since the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade last year.

Former State Rep. Pat Smith, D-Baton Rouge, sponsored multiple bills to mandate sex education in Louisiana schools. Her attempts were unsuccessful. (Photo by Brett Duke, The Times-Picayune archive)

Former state Rep. Pat Smith, D-Baton Rouge, carried a sheaf of bills during her legislative terms that would have implemented mandatory sex education in schools, while still allowing parents to opt their kids out.

She argued that comprehensive sex education could improve Louisiana’s dismal outcomes on multiple fronts: fewer teens might get pregnant or have sexually transmitted diseases, and the government would spend less money taking care of them.

Studies have found that group-based, comprehensive sex ed lowers rates of teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases. Physicians’ groups like the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists support comprehensive sex ed.

Smith also wanted to teach children about unsafe situations, consent and help them to recognize if someone in their home was abusing them. The Louisiana Public Health Institute surveyed 600 parents across the state and found 74% believed schools should offer sex education.

But the bills faced backlash.

Angela Bess talks during an OMG Girlz meeting at the OMG Girlz clubhouse on Tuesday, November 28, 2023.

The influential Louisiana Family Forum and other religious groups argued that schools were the wrong place for children to learn sex education, and that guidance should come from parents, churches and other community organizations. They said that teaching kids about contraception might encourage promiscuity.

Some parents also said they worried about leaving such important moral instruction in the hands of the state — a theme that has echoed in recent efforts to roll back sexual health instruction in other states.

Smith also tried to change Louisiana’s approach to surveying teens about risky behavior. The CDC’s youth risk behavior survey asks Louisiana teens about drug and alcohol use, dating violence, suicide and depression.

Beverly Warren speaks during an OMG Girlz meeting their clubhouse on Tuesday, November 28, 2023.

But Louisiana has opted out of allowing them to answer questions about whether they were having sex and using birth control.

Louisiana is an outlier for not allowing that portion of the survey: Even Mississippi and Arkansas use it. Smith couldn’t get lawmakers here to follow suit.

“Nobody has picked up the banner again,” she said.

South Carolina stands out in Deep South

Physicians and sex educators say they often hear from teens that they’re getting their information about sex from social media, especially TikTok, where the lessons may be far from medically accurate. Old myths about ways to avoid getting pregnant — having sex in hot tubs, while standing up or while menstruating — persist.

“They all have such a different knowledge level, which is more confirmation for me that we’re not teaching this information in a comprehensive way,” said Dr. Stephanie Shea, a Tulane pediatrics resident who works closely with adolescents.

Syndi Wheeler, left, decorates a white board before an OMG Girlz meeting while founder, Sashika Baunchand, tells a story at the OMG Girlz clubhouse on Tuesday, November 28, 2023.

Shea has been comparing policies in the Deep South states of Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi and South Carolina. Three of those states mandate sex ed in schools: Mississippi, Georgia and South Carolina. All five states require that sex ed, if taught, stresses abstinence.

Shea said Louisiana might look to South Carolina as a better model of how to implement and evaluate sex-ed programs. While South Carolina still ranks above the national average for rates of sexually transmitted diseases and teen pregnancies, its rates are well below Louisiana’s.

Ashton Galbo poses with her seven-year-old daughter, Harper-Layne, in their home on Thursday, November 30, 2023.

In 2013, South Carolina commissioned a study of how the state’s past 25 years of sexual health education had been implemented. It found the majority of the state’s school districts were out of compliance with the law, teacher training and instructional materials were inadequate and more. The findings prompted changes.

Louisiana, meanwhile, has not looked closely at how its current policies are affecting outcomes.

“South Carolina has been able to use those bad health outcomes to drive policy,” Shea said. “Louisiana’s health outcomes aren’t driving changes.”