Gov. John Bel Edwards on Thursday morning officially broke ground on Louisiana's most ambitious wetlands-restoration effort yet at a ceremony near Ironton on the west bank of the Mississippi River.

Decades in the making, the massive $2.9 billion Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion aims to recreate the river's ancient, natural land-building processes by diverting a portion of the Mississippi's freshwater, sediment and nutrients into the Barataria Basin. The hope is that it will rebuild up to 21 square miles of land and wetlands in Jefferson and Plaquemines parishes over the next half-century.

"At the end of the day, the premise of the project is we want to reconnect the Mississippi River with our coastal areas so that we can replenish the marsh and grow the land that we've lost," Edwards told reporters after a ceremonial overturning of dirt. "And this project promises to do that, from a minimum of 20 square miles to a maximum of 40.

"We will create as many acres of coastal marsh out of this project than we have over the last eight years from all of the projects we’ve done, together. And it's critically important because you have to protect population centers, you have to protect critical aspects in terms of infrastructure and the economy, and you’ve got to have a storm buffer between the Gulf of Mexico and those people and those cities. You don’t have it if you don’t rebuild the marsh."

Hundreds take shelter from the summer sun at the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion groundbreaking ceremony south of Belle Chasse, Louisiana on Thursday, August 10, 2023. (Photo by Chris Granger | The Times-Picayune | NOLA.com)

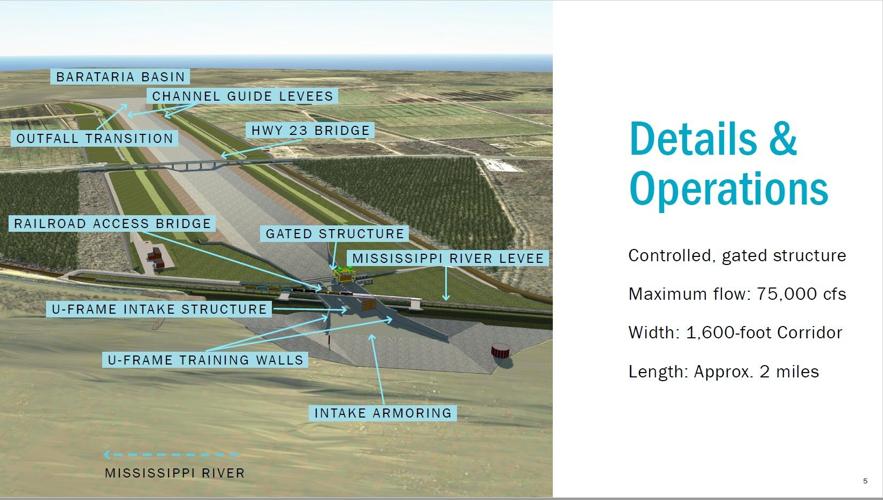

The diversion will include a two-mile channel built along a 1,600-foot corridor between the river and the basin, with a complex structure of gates on the river side and a wide outfall on the basin side, aimed at moving the sediment and water into areas of open water and existing wetlands when it is completed in about 5 years.

The state first requested permits for the project in 2016, but its origin actually stretches back to the end of the 19th century, when scientists first raised concerns about Mississippi River levees cutting off the supply of sediment that built the state's coastal wetlands, said Bren Haase, chairman of the state Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, which is building the diversion.

Proposals for diversions similar to Mid-Barataria were included in state plans beginning in 1998 and in its first coastal Master Plan in 2007.

The diversion is designed to operate between December and June when the water flow is at 450,000 cubic feet per second or greater. It will be designed to allow a maximum flow of 75,000 cfs to enter the basin, likely only during high-river years when the river's flow reaches 1 million cubic feet per second or more.

During low periods, as much as 5,000 cfs will still flow through the channel to keep it clear of sediment.

The project is the state's largest effort to date to reduce the effects of subsidence, sea level rise and tropical storm and hurricane damage, which together have led to the loss of more than 2,000 square miles of the state's coastline since the 1930s.

Artist's rendering of the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion (Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority)

The project has no shortage of critics. They include oyster growers, shrimpers and other fishers whose catches are likely to be dramatically affected by the diversion's freshwater flow, and a number of politicians, including Lieutenant Gov. Billy Nungesser, who has said the money for the project would be better spent on other projects that build land more quickly.

St. Bernard Parish Council member Kerri Callais, who also serves on the board of Save Louisiana Coalition, a key opponent of the project, cited the environmental impact statement accompanying the permits issued for the project by the Corps of Engineers in arguing against the project. It says the diversion will cause "major, permanent adverse impacts" to oysters and brown shrimp, "higher prices for locally caught seafood," and adverse impacts on spotted sea trout, better known as speckled trout.

"We are wasting valuable coastal restoration dollars that could be used on proven projects like marsh creation, sediment pipelines, and barrier islands," Callais said.

This graphic accompanying the Louisiana Trustee Implementation Group's Mid-Barataria Diversion restoration plan shows the study's conclusions on the project's environmental pros and cons. The trustees have agreed to pay $2.26 billion of the construction cost of the project, using BP spill natural resource damage funds. The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation has agreed to pay $660 million of the construction cost, with the funds coming from BP and Transocean criminal fines for the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

But others point to broad support for the project from a variety of scientists and scientific studies, including the environmental impact statement. Their consensus is that the diversion's benefits will outweigh its effects; they also point out that the state already is spending much of its coastal restoration money on projects that dredge sediment from the river and pump it into open water to build new lands.

They also point out that the diversion's continued flow of sediment and nutrients will extend the life of such pump-and-fill projects beyond their expected 20-year lifetimes.

In addition, the land built by the project is expected to reduce storm surge on nearby hurricane levees by as much as 6 inches.

At the groundbreaking ceremony, state Sen. Patrick Connick, whose district includes parts of Plaquemines and Jefferson parishes, said that while the project will cause problems for commercial fishers, there’s no choice but to build it.

Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards, right, talks with former U.S. Senator Mary Landrieu at the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion ground-breaking ceremony south of Belle Chasse, Louisiana on Thursday, August 10, 2023. The long-needed diversion will one day deliver sediment and nutrients from the Mississippi River into the disappearing south Louisiana coast just south of New Orleans(Photo by Chris Granger | The Times-Picayune | NOLA.com)

“It’s no surprise to any of us that this project will change the landscape of the marsh, and it has to change the landscape of the marsh,” he said. “The entire Terrebonne estuary is in danger, and with this project, we’ll be able to save it."

And U.S. Rep. Garret Graves, R-Baton Rouge, who served as chairman of the state coastal authority before going to Congress, said in a taped message that research conducted on the diversion proposal for years showed it would be successful.

"What we did in this case is we relied on the scientists and let the science drive. We didn’t let politics enter into it," Graves said.

This schematic map shows the features of the proposed Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion, including new wetlands, in yellow, created with sediment dredged from the diversion path. (Louisiana BP Trustee Implementation Group)

Over time, the diversion will improve freshwater fisheries, Haase pointed out, which will also result in increased economic benefits. And the project's construction -- which is expected to take about five years -- will produce an estimated 12,400 jobs and $1.4 billion in increased sales for the region, according to recent economic studies.

Site preparation activities actually began in June.

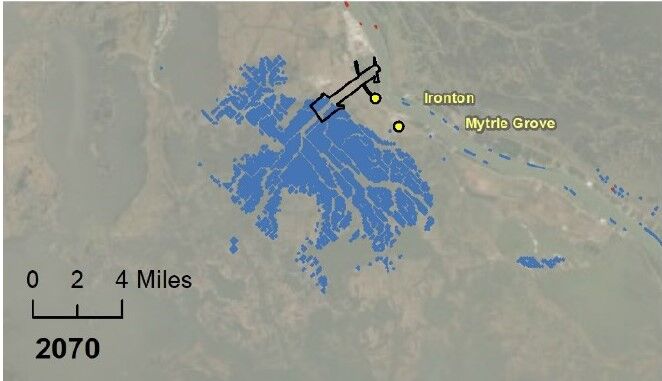

This map shows the expected land gain resulting from operation of the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion through 2070. (Army Corps of Engineers)

Entergy has started relocating utility poles and other equipment, and a temporary rerouting of La. 23 will be built this fall, along with the beginning of construction of a permanent bridge replacement across the diversion. A new railroad bridge also will begin construction atop the diversion site in the next few months.

CPRA has set up a special hotline for construction-related problems: 504.946.9001.

The state has set aside $360 million of the project's construction cost for projects aimed at mitigating the impacts on existing commercial fisheries, and to deal with potential flooding concerns of residents and businesses that are outside hurricane levees south of the diversion.

The $3 billion Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion will help slow land loss on Louisiana's coast, but the threat to dolphins is among the drawbacks.

Some of the funds also will be used to attempt to reduce what could be a virtual elimination of all bottlenose dolphins in the Barataria Basin during the first few years of the diversion's operation, the result of the dolphins' expected illnesses from freshwater exposure.

In June, surveying began to identify flooding risks to buildings outside the levee system south of the diversion. The results will be used in discussions with residents and businesses of possible mitigation projects during meetings with individual landowners during the last quarter of 2023 and the first quarter of 2024.

Some projects aimed at elevating roadways and bulkheads between Myrtle Grove and Happy Jack are already underway, CPRA officials said.

While the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion will increase land area near its path, reduction of sediment in the Mississippi River will reduce size of wetlands in the birdfoot delta near its mouth.

Over the past year, CPRA officials and contractors have also met with fishers to discuss potential projects to mitigate the effects of the diversion's freshwater on oysters, shrimp and finfish.

Project's construction cost rises to $2.92 billion. Its aim is to help slow the land loss devastating the coast.

Most existing oyster leases are likely to become too fresh for oysters to survive. The growth of juvenile brown shrimp into adults large enough to catch is likely to also be delayed by the freshwater, requiring shrimpers to travel longer distances.

The state will spend $6 million, with assistance from the state Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, to add cultch -- oyster shells and rock material on which baby oysters can grow -- to public oyster seed grounds, and $1 million for alternative off-bottom oyster culture projects.

This map shows the land loss expected in southeast Louisiana with no addition restoration efforts, including the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion, through 2070. (Army Corps of Engineers)

The state also is studying the expected replacement of state-owned water bottoms presently leased to oyster growers with water bottoms in areas that will be salty enough for oysters after the diversion begins operation. The state expects to provide money to place cultch at the new locations.

Another $2 million in mitigation money will pay for additional marketing of Louisiana wild-caught shrimp.

Louisiana’s ambitious and expensive plans for restoring the coast received strong backing fr…

The state also will spend $1 million, in coordination with Plaquemines Parish, to improve access for subsistence fishers -- fishers who are catching fish just for the families -- on the west bank, including improvements to existing or new boat launches and fishing piers.

And on Thursday, the Department of Wildlife & Fisheries announced it has received $58 million in additional federal disaster assistance funds related to 2019 freshwater flooding in the Mississippi and Atchafalaya river basins in the state, with that money also to be used for a variety of vessel access and dock improvements, oyster cultch and for research into oyster resilience, including in the Barataria Basin.

Grant money helps expand practice of raising oysters in floating cages

One benefit expected to result from the river’s freshwater being used to build new wetlands and improve existing wetlands is that nutrients in the water, including phosphorus and nitrogen, are likely to be taken up by that vegetation before reaching the Gulf, Haase said. That could help reduce the size of the annual low-oxygen dead zone along the state’s coast, which is caused when the nutrients create algae blooms that die and sink to the bottom, where they decompose and use up oxygen in the coastal bottom waters.

The state also will focus part of its mitigation funds on reducing the loss of wetlands in the part of the southernmost wetlands that are part of the river's "birdfoot" at its mouth, which are expected to shrink because the diversion will capture sediment keeping them above water.

The state will focus on creating more crevasses along channels running through existing delta, to encourage the building of more land.

The $2.92 billion construction cost for the diversion includes $2.26 billion provided by federal and state trustees overseeing the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill natural resource damage assessment settlement, and $660 million from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, with the funds coming from criminal fines assessed to BP and Transocean.

The project is being built under a state-allowed “construction manager at risk” program, which requires the construction manager firms to deliver the project within a guaranteed maximum price, working with designers throughout he project design process.

The lead construction manager firms are St. Louis, Mo., based Alberici and Atlanta based Archer Western, a subsidiary of Walsh Construction. There are 16 subcontractor firms involved in the construction project.

The lead design team firm is Dallas-based AECOM, which is working with 15 subcontractors. AECOM also is the lead construction services contractor, with 19 subcontractors.