This is the second story in The Guardians, a 6-part series highlighting those dedicated to saving and passing down New Orleans' unique heritage.

Artist Willie Birch is on a mission. He invested his nest egg in a sometimes-forgotten patch of the 7th Ward that he considers a hidden gem. Birch says the neighborhood is a perfect example of the modest urban architecture built and occupied by the descendants of former enslaved Africans, plus immigrant Irish and Sicilians, the working-class folk that helped make New Orleans what it is.

Birch, 81, plans to spend his waning years bathing in the history of the neighborhood, documenting its present and trying to ensure its future.

“This place, I don’t know any place like it,” he said.

Birch is one of New Orleans’ most accomplished visual artists. His sculptures, paintings and drawings appear in major collections, from the New Orleans Museum of Art to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, to the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis. He regularly sells works for tens of thousands in an upscale Julia Street gallery. Which is a particular triumph for somebody who grew up in the Magnolia housing development back in the Jim Crow era.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, the fundamental purpose of Birch’s art has always been to preserve the Black experience. Especially the normal, neighborhood moments that characterize life in New Orleans. Birch’s friend and fellow artist Ron Bechet, a Xavier University professor, calls Birch a latter-day Courbet, the 19th century French artist whose paintings of the working class were a revelation to the aristocracy.

Artist Willie Birch walks along Old Prieur Street in New Orleans on Wednesday, November 29, 2023.

Birch said his mother hoped he’d grow up to be a doctor or a lawyer, but he was an artist from the start. When his detailed sixth grade drawing of his grandfather’s farm was lauded by his teachers and schoolmates alike, the die was cast. In high school, he was enlisted to paint protest signs for picketers calling attention to discrimination at a grocery store.

After joining in some further civil rights protests in New Orleans, Birch served a stint in the Air Force, mostly in Holland, then graduated from Southern University in New Orleans and later received a Master of Fine Arts degree from the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore. For a time, he was a starving artist in New York City, before his career got some serious traction. In 1993, he came back to New Orleans on a prestigious Guggenheim fellowship.

Something to feel good about

Birch was a star upon arrival. His expressionistic papier-mâché sculptures of Black American genre scenes and historic subjects were snapped up by collectors. Back home, Birch could have chosen to live in a neighborhood with few sirens in the night. But Birch bought a spot on North Villere Street in the 7th Ward instead, where he’d be closest to the aspects of Crescent City culture he loved most, including Mardi Gras Indians.

The Acadiana Center for the Arts in downtown Lafayette recently opened an exhibit of works by New Orleans artist Willie Birch. The exhibit tells the story of American freedom from the African-American perspective. Celebrating Freedom: The Art of Willie Birch was originally scheduled to open in New Orleans, but was delayed due to Hurricane Katrina.

One of his proudest moments, Birch said, was one Mardi Gras morning, when the late Big Chief Tootie Montana, a revered Black masking Indian, clasped his hand and raised it up in a salute from one master artist to another.

Birch said he got some important pointers from Montana. For instance, the Big Chief told him that he created his intricate beaded and feathered suits “for the community.” So that when he debuted his creations on Fat Tuesday, people in the neighborhood “would feel good about themselves.” For Birch, the lesson sunk in. Maybe his art could have a similar effect.

Feeling The Cut

As Birch reached his mid-70s, he naturally started considering his legacy and his last hurrah. The North Villere Street place wasn’t big enough for his plans.

Artist Willie Birch poses for a photograph as community members attend the opening of the Old Prieur Community Memory Garden in New Orleans, La., Saturday, Nov. 2, 2019.

“I was looking for a place more permanent,” he said, “that could expand.” He said he planned to “create an estate and an archive for my work,” in what he calls "the heart of the poor community.” While hunting the Latter and Blum real estate offerings, he found an interesting piece of property on Old Prieur Street.

The lot was located within an odd knot of streets where two much larger street grids imperfectly intersect. The place is sort of an island of its own, known as The Cut. There were four small shotgun houses on the property, plus two empty lots.

Birch had to buy everything or nothing; that was the deal. He said he haggled for the best price and paid cash for the whole shebang. The little houses were a mess at the time, with holes in the floors, trash out the back door and rats. But Birch invested more of his savings to stabilize them. They aren’t palaces, but they aren’t deteriorating anymore either.

Artist Willie Birch walks in an art garden near to his studio in New Orleans on Wednesday, November 29, 2023.

Paying respect

He chose one house to be his home, installed his studio in another, and rented out the other two. It didn’t take long for Birch to discover he wasn’t cut out to be a landlord, so he now plans to use the other small houses for artistic endeavors. The truth is, the whole property is an artistic endeavor, an act of personal expression and an act of preservation, in a part of town where preservation isn’t always a priority.

“Willie was looking for some place that spoke to him, a neighborhood where he could make a difference,” said Bechet. He set out to “be a guardian” of the precious place. When he first moved in, Bechet said, Birch cut down the weeds in the corner lot beside his houses with a sling blade, a cross between a machete and an ax.

“Can you imagine cutting the grass with a sling blade, at his age?” Bechet asked.

It was a measure of his commitment. Birch keeps the weeds at bay, and he doesn’t mind cleaning litter from the street. “People throw stuff on the ground, I pick it up,” he said. “I don’t feel bad about it.”

Artist Willie Birch is seen in his studio in New Orleans on Wednesday, November 29, 2023.

He also doesn’t mind asking neighbors to turn down loud music, if he’s trying to work at his computer. But he tries to be civil about it. Birch said he hopes to inspire respect for The Cut without disrespecting anyone in the process. He believes both the area and the people ought to be revered.

“They could be anyplace else,” Birch said of his neighbors, “but because of racism, class and the way we separate each other, they’re here.”

Imagine

From the beginning, outdoor sculpture was a big part of the picture. Birch converted the lot that he had manually cleared with a sling blade into a community garden studded with modern art contributed by fellow artists. Not everybody got it, at first, he said, but it certainly inspired contemplation.

Birch produced his own outdoor sculptures as well. When workmen were shoring up the foundation of one of Birch’s houses, they planned to throw the debris they’d found under the 130-year-old building into the dumpster. But Birch asked them to just toss the junk into the adjoining empty lot instead.

You see, junk isn’t junk to Birch, it’s a trove of history and metaphors.

As he led a tour of his collection of yard art on a recent afternoon, he pointed out the various sculptures he’s created out of practically nothing. From a rusted step stool and broken windows, Birch produced a self-styled shrine for children lost to gun violence. He wove reeds into stalactite shapes that hang eerily from a fence, like wandering spirits. And he left a piece of baby-blue gutter that blew off one of the houses lying in the grass right where he found it, jutting up at a 45-degree angle as an accidental phallic symbol.

Artist Willie Birch walks in an art garden near his studio in New Orleans on Wednesday, November 29, 2023.

In the midst of it all, Birch — with Bechet’s help — built a traditional bottle tree, made from broken pecan branches tipped with bottles and the beer cans that used to litter the street. The crate from which the bottle tree springs is labeled with the word “Imagine.” Passersby can read it from the street.

Bottle trees are a custom believed to have come to the South from the Congo with enslaved people. Birch points out that an avant-garde White artist named Robert Rauschenberg achieved superstardom in the 1950s displaying abstract assemblages of junk to smitten artworld audiences. But how, Birch wants to know, did Rauschenberg become a darling of the museums, just by doing the sort of yard art that African Americans had been doing for as long as anybody can remember?

Making a family album

When he’d first returned to New Orleans in the early 1990s, Birch was known for the brilliant colors he applied to his paper mache sculptures. But soon after, his style began to shift. First of all, Birch said, he recognized that big-time Big Easy artists John Scott and Ida Kohlmeyer were already known for their blazing palettes.

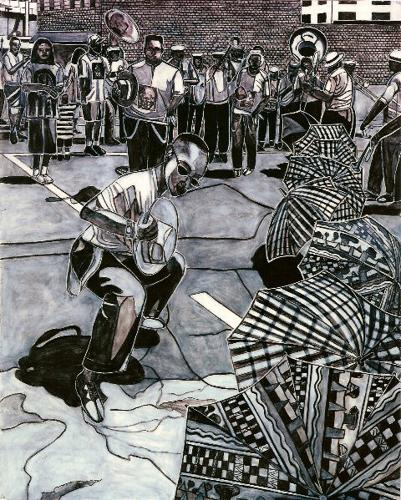

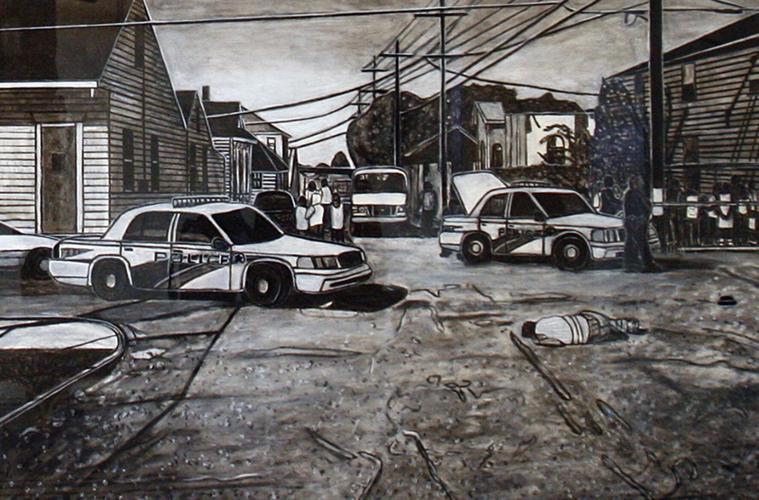

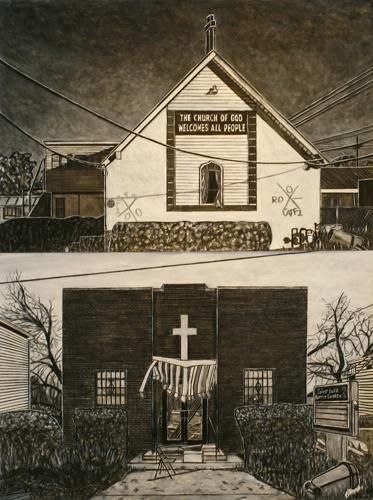

Prospect.1 artwork by Willie Birch

Birch didn’t want to slip into that well-worn groove. So, he went in the exact opposite direction. There’d be no more high-key colors in his artwork — just black and white. Serious, severe black and white. For Birch, it was basically an optical shift. But there was more going on.

Birch had begun drawing relatively realistic scenes from Black neighborhood life. Despite their sometimes-huge scale, and despite Birch’s gritty style, his black charcoal drawings augmented with white paint had the incidental, intimate feel of the snapshots you might find in old family albums. In a way, Birch was producing a family album of the backstreet New Orleans community he loved, preserving its history.

As an artist of his stature, Birch said he realized “nobody threw away Willie’s work.” So, nobody was going to throw away the world he was rendering.

His giant drawing of a pair of crutches somebody discarded on the sidewalk near his Old Prieur Street houses would surely end up in an art collector’s home. His enormous, three-part portrait of a Black woman, whose commanding posture indicates she isn’t in the mood for any shenanigans from anybody, might find its way into a museum. And his drawing of saxophonist Kidd Jordan’s funeral convoy sloshing through a flooded Crescent City street would surely be added to some musical archive.

STAFF PHOTO BY MICHAEL DEMOCKER Saturday, October 6, 2007 Arts patrons stroll through the Willie Birch exhibit, "Home Sweet Home" at the Arthur Roger Gallery on Julia Street. The exhibit was part of the 18th annual Art for Arts' Sake, the fall art celebration featuring gallery and museum openings, live music, and food in the New Orleans Art District as well as several other locations citywide.

The greatness of these people

Not long after he settled into The Cut, Birch was invited to be an artist in residence at Isidore Newman school, which is a considerable distance from the heart of the poor community. He planned to provide an exhibit and instruction at the private Uptown campus. But he also arranged for the kids to visit his 7th Ward enclave to discuss drawing, history and gentrification.

Kathryn Scurlock, who manages Newman’s visiting artist program, said that Birch immediately began sharing his vision of using the tools of art to benefit a community. Fifth graders visited The Cut, where they listened to Birch describe the Mardi Gras Indian tradition and other aspects of New Orleans culture that arose in neighborhoods like his.

The students also studied the relationship of Birch’s drawings to the area, and produced artworks and essays about the experience.

Paint brushes are seen in the Willie Birch's studio in New Orleans on Wednesday, November 29, 2023.

It was a message he's imparted throughout his career: Look closely at the less-celebrated neighborhoods of the city, where generations of unrecognized residents overcame hardship to help produce our way of life. That is worth saving, too.

“This city is so special,” he said, but “all this can be lost if we forget the greatness of these people.”

Birch plans not to forget.