New Isle, the country’s first federally funded resettlement site for a community threatened by climate change, is nearly doubling in size.

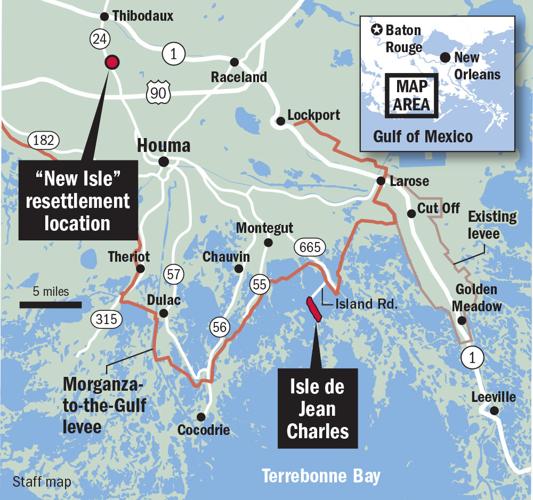

The subdivision in the small community of Schriever, about five miles south of Thibodaux, is adding 27 single-family homes to the 34 that were given to the former residents of Isle de Jean Charles, a Native American community that’s been ravaged by storms, coastal erosion and rising seas.

“To have their whole community uprooted has been hard,” said Nicole Barnes, executive director of Jericho Road Episcopal Housing Initiative, a New Orleans affordable housing organization. “We wanted them to have the same sense of community, same sense of family and support systems here.”

On Tuesday, Barnes toured one of the partially constructed homes with officials from the Louisiana Housing Corp., which is leading New Isle’s second phase. Barnes expects to have the first 19 homes completed by March.

The New Isle project was funded with a $48 million U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development grant in 2016. The grant covered the purchase of the 515-acre New Isle property and the construction of homes, roads and other infrastructure.

The project’s first batch of homes was completed by the state Office of Community Development in August 2022. The 34 houses were given for free to people who had been displaced from Isle de Jean Charles after Hurricane Isaac in August 2012.

Houses in the second phase will cost residents between $150,000 and $175,000. Preference will be given to former island residents with low and moderate incomes, but this phase and possible later ones will likely be opened to income-qualified Louisianans who have no connection to Isle de Jean Charles.

"Bert" Naquin serves birthday cake for her 66th birthday in her new kitchen in phase one of New Isle. Construction of the second phase of New Isle is underway in Schriever, La, by Louisiana Housing Corp. Tuesday, November 13, 2023. Residents of the Jean Charles Choctaw Nation were resettled from Isle de Jean Charles to higher ground in phase one of the massive project.

About $5 million is being spent on the first 19 homes in phase two, or about $263,000 per home. A $1 million line of credit from Enterprise Community Partners and proceeds from the sale of the 19 homes will be used to build eight more homes, for a total of 27.

The homes’ roofs will be fortified to withstand hurricane-force winds, and lighting, appliances and plumbing are all designed to boost efficiency and lower utility costs, Barnes said. She hopes to eventually add an array of solar panels to produce energy for New Isle and possibly other buildings in Schriever, but details, including funding, haven’t yet been worked out.

The initial plan for phase two was to offer land and let residents build their own homes, but that proved expensive and complicated for would-be residents, Barnes said.

Leaders with the Jean Charles Choctaw Nation, a tribe that has seen almost all of its members leave its namesake island in recent decades, said most people signing up for phase two live in inland urban areas rather than higher-risk coastal communities hit hard by Hurricane Ida and other recent storms.

“They’re signing up people from Houma and Thibodaux, but the people down the bayou — in lower Pointe-aux-Chenes, Montague, lower Dulac — they’re in desperate need with desperate problems,” said Albert Naquin, a member of the tribe’s council and its former chief.

Construction of the second phase of New Isle is underway in Schriever, La, by Louisiana Housing Corp. Tuesday, November 13, 2023. Residents of the Jean Charles Choctaw Nation were resettled from Isle de Jean Charles to higher ground in phase one of the massive project.

The tribe hopes to raise several million to buy and develop a second relocation site with about 75 homes. Naquin said they hope to begin fundraising early next year. No site has been selected.

The New Isle project has traveled a long and rocky road. Initiated by the tribe in 2002, the project was taken over by the state once the grant was awarded, and tribal leaders were pushed out of decision-making. While the tribe had hoped to quickly relocate members to 120 new homes, the process took nearly seven years and resulted in far fewer homes.

Uncompleted elements of phase one include three homes, a community center, playgrounds, retail structures and a marketplace.

New Isle resident Chris Brunet has mixed feelings about the project. The community he grew up in is reforming at New Isle, but some of the year-old homes have required repairs that have been slow to come.

Construction of the second phase of New Isle is underway in Schriever, La, by Louisiana Housing Corp. Tuesday, November 13, 2023. Residents of the Jean Charles Choctaw Nation were resettled from Isle de Jean Charles to higher ground in phase one of the massive project.

“I’m grateful for the house,” he said. “But there have been some issues that will hopefully be addressed.”

Brunet said his flooring was damaged by moisture seeping in through cracks. Other residents report water damage from faulty plumbing, cracked walls, poorly installed light fixtures and rainwater pooling under homes.

The community is starting to settle in, Brunet said. He enjoys seeing children, who had been an increasingly rare sight on the island, zipping around New Isle on bikes.

“Here, it’s all about sitting on the front porch, talking and the children playing,” he said. “It’s good to know the people next door are the people you’ve known all your life.”