At St. Martinville High School in the mid-1980s, Jeff Landry was known as a chatterbox with boundless energy who made friends easily.

However, he never stood out academically, and he never held leadership positions in social or student government groups.

After graduating from high school, he worked in a sugar cane field near his home.

“He was a very average, normal young man,” said Carroll Delahoussaye, his football coach. “He was the last one you thought would have been governor. He never seemed to have that sort of ambition.”

From left to right: Al Landry, Becki Landry, Jeff Landry, Edna Landry, Nick Landry, Ben Landry and Andrea Landry. Undated photo.

It wasn’t until later — after swapping out the cane field to work in law enforcement and serve in the military — that Landry would learn firsthand from two men how politicians can befriend constituents, solve problems and use their power to bend people to their will.

The men — then-St. Martin Parish Sheriff Charles Fuselier and then-state Sen. Craig Romero — would change his trajectory, but not immediately.

He would start his own business, finally graduate from the University of Southwestern Louisiana (now the University of Louisiana at Lafayette), marry into one of the richest families in Iberia Parish and lose his first race. But in 2010, he broke through by winning a congressional race that would enable him to knock off the incumbent attorney general five years later. Along the way, he would demonstrate an ability to see political opportunities that others missed and use his Cajun charm to ingratiate himself with older wealthy men who would finance his campaigns.

On Jan. 8, Landry will end eight years as attorney general and apply the lessons he learned to his latest, and largest, endeavor: leading a state with 4.5 million residents.

“Certainly, being governor of the state is aspirational for anyone who loves politics,” Landry said in one of two interviews. “But I don’t know that I ever really believed that I could ever become the governor. As I went from one place to another, it just worked out that way.”

How Landry leads Louisiana will become clear in the coming weeks and months. But in the meantime, his path from a small town to the Governor’s Mansion, full of unconventional twists and turns, provides clues about what sort of governor he’ll be.

Small-town childhood

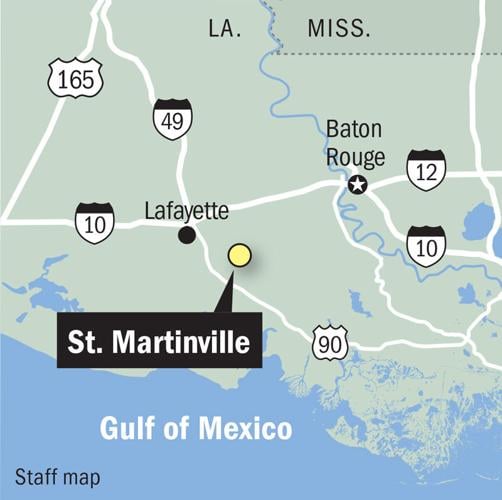

Jeffrey Martin Landry’s story begins in St. Martinville, the seat of St. Martin Parish, a 30-minute drive southeast of Lafayette.

The town is bisected by the Bayou Teche and is surrounded by sugar cane fields.

His parents, Al and Edna Landry, had been high school sweethearts in St. Martinville and settled in town after graduating from the University of Southwestern Louisiana.

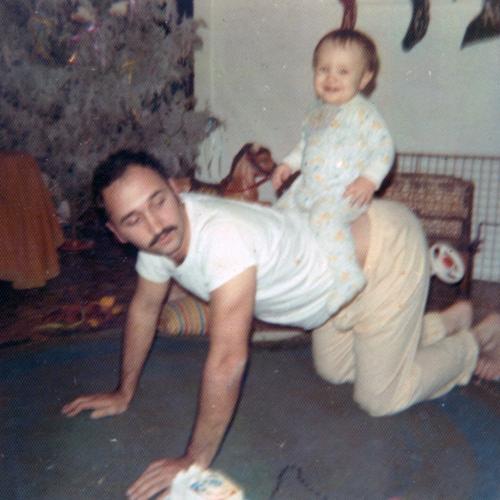

Jeff was born on Dec. 23, 1970, the oldest of four children in a devoutly Catholic family. They grew up in a modest house that’s worth an estimated $165,000 today.

Al Landry was a small-town architect and is “a complete introvert,” in his son’s words.

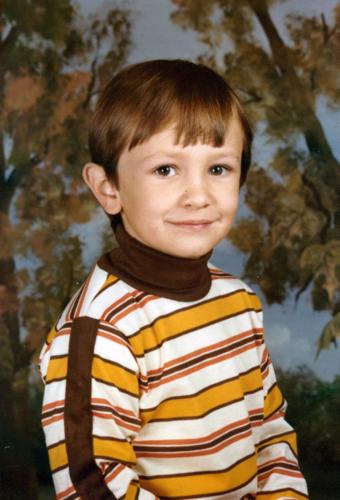

Jeff Landry is seen playing as a boy in this undated photo. The attorney general will be sworn in as Louisiana's 57th governor on Monday, Jan. 8, 2024.

Edna Landry taught basketball and religion at private schools but was talkative and personable, traits her son inherited. She felt a calling to volunteer for practically any cause to better St. Martinville, but had a “passion” for teaching children, Black and White, how to swim, Jeff Landry noted.

“She was like an angel. It didn’t matter, day or night, if she thought she could help someone less fortunate, she would,” said Guy Cormier, a childhood friend who went on to be elected president of St. Martin Parish and now heads the Police Jury Association of Louisiana. (Edna Landry died in 2019.)

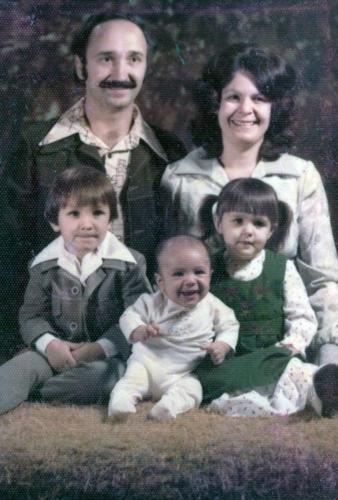

From left to right: Al, Edna, Jeff, Nick and Becki Landry, undated family photo. Jeff Landry will be sworn in as the 57th governor of Louisiana on Monday, Jan. 8, 2024.

As a boy, Landry and his buddies swam and fished in the bayou, hunted on weekends and during the summer and rode bikes to Vee’s Five & Dime, which had an aisle of candy that cost 1 to 5 cents apiece.

If parents wanted to give their kids a special treat, they would take them for burgers at the Sonic on the north side of town.

When Landry was in high school, only 15 years had passed since St. Martin Parish’s schools had desegregated. The high school was split about 50-50 between Black and White students, but the July 4 fais do-do and the annual roasting of a pig in Magnolia Park were nearly all-White affairs.

At Friday night’s football games, Black fans sat in one set of bleachers on the home side of the field, while White fans congregated in another one. Each race organized its own high school prom.

But Landry had Black friends over to his house all the time to play in the backyard pool his mother had built to teach swimming lessons, remembered Marcelle Bienvenu, his aunt.

“Jeff didn’t see race. He had just as many White friends as he did Black friends,” added Jason Willis, the African American mayor of St. Martinville, who grew up with Landry.

Wearing No. 38, Landry played wideout on the high school football team, starting a few games as a senior.

“He was average at best in athletic ability and coordination,” said Delahoussaye, who coached the St. Martinville team for 31 years. “But he had, it’s a cliché, the heart of a lion. He’d tussle with the better players and give it everything he had.”

But Landry didn’t give everything he had in the classroom, he acknowledged in an October interview while explaining why he had no interest in going to college right after high school.

“I didn't like school,” he said. “I just wasn't interested. I think school is overrated to begin with, you know? If I wanted to learn something, I just go do it myself.”

Landry enrolled in the Louisiana National Guard during his senior year in high school at the urging of his mother who hoped it would instill discipline and give him a path forward.

From left to right: Edna, Jeff and Al Landry in Washington D.C. Undated photo. Attorney General Jeff Landry will be sworn in as the 57th governor of Louisiana on Monday, Jan. 8, 2024.

After graduating from high school, Landry worked in a local sugar cane field, clearing drainage ditches with a shovel and driving a tractor for $4.50 per hour. He sweated during the warm days and was soaked when it rained.

Over the next several years, while also fulfilling his Louisiana National Guard duties, he worked as a police officer in the village of Parks in St. Martin Parish and as a parish sheriff’s deputy, initially in the jail and later serving bench warrants. When he drove around the parish as a deputy, he liked the freedom of not being stuck behind a desk and being able to talk to different people throughout the day.

Landry had had another reason for not wanting to go to college immediately.

“I never liked my parents paying for anything,” he said. “I did not want my mom and dad to do that because then they'd want to control me.”

Landry’s service in the National Guard solved that problem because it would cover his college costs. He enrolled at USL in 1990, but attended only part-time so he could work.

Discovering politics

From the time that Landry was 10, one man dominated St. Martin Parish: Charles Auguste Fuselier. He succeeded his father as sheriff in 1980 and held the job for the next 33 years.

Gruff, gregarious and weighing at least 300 pounds, Fuselier broadened the role of the sheriff’s department beyond law enforcement duties. Fuselier hosted weekly suppers for the elderly, assisted people who needed a hand and offered his sought-after blessing for would-be candidates in the parish.

“He was big in every way you can measure a man. Everyone looked to the sheriff for direction,” said Allan Durand, a Lafayette attorney from St. Martinville whose father was Fuselier’s chief deputy.

Fuselier took a special liking to Landry, hiring him to be a sheriff’s deputy in May 1992.

Then-St. Martin Parish Sheriff Charles Fuselier stands by the doorway of one of the holding cells on Tuesday, Sept. 12, 2000, in the juvenile detention center near St. Martinville. Fuselier was one of Attorney General Jeff Landry's mentors. Landry will be sworn in as the state's 57th governor on Jan. 8, 2024.

That October, Fuselier sent Landry to New Iberia on an important assignment. Craig Romero, the Iberia Parish president, was running for the state Senate, having just overcome a residency challenge and now needing to make up lost time. It was only two weeks before the primary.

Landry knocked on Romero’s door on a Saturday morning and explained that Fuselier had sent him there to take Romero to St. Martinville to introduce him to voters.

At stop after stop in St. Martinville, Romero couldn’t believe what he saw.

“Everywhere we walked in, they didn’t just reach out to shake his hand,” Romero recalled years later. “They’d walk up to give him a full hug like he was their child. I said to myself, ‘People love this young man.’ He was the best resource anybody could give me.”

In an eight-candidate field, Romero won 43% of the vote in St. Martin Parish, better than the 35% he collected in Iberia Parish. Romero led the primary and then won the election to the Senate when the second-place finisher withdrew in the runoff.

In the following years, when the Legislature was in session, Landry would drive to Baton Rouge to serve as an aide to Romero. The duties could be menial — getting coffee for the senator or his colleagues, taking Romero’s children to the Governor’s Mansion to swim or taking documents to the House that Romero needed a representative to sign.

Port of Iberia Executive Director Craig Romero speaks during a luncheon Friday, March 19, 2021, at the Port of Iberia offices in New Iberia, La. Romero is a mentor of Attorney General Jeff Landry, who will take office as the 57th governor of Louisiana on Monday, Jan. 8, 2024.

Landry would bring cracklins and boudin from St. Martin Parish for Senate staffers and sergeants at arms, and at night he would organize cookouts of Cajun food at Romero’s Senate-provided apartment at the Pentagon Barracks.

Landry stood out among the legislative aides.

He found that he liked politics, in part because it served his short-term attention span.

“It was fun, it was exciting,” he said. “It fit my ADD because it was constant chaos and movement.”

While Fuselier introduced Landry to local politics, Romero gave him a taste of the state political scene. Romero was known for his willingness to campaign hard for votes at home and campaign hard in Baton Rouge for available money to fund projects in his Senate district.

Romero also faced regular accusations that he steered government work to his and his family’s businesses. He dismissed the accusations as political attacks but was charged and fined for violating state ethics codes in the 1980s and 1990s.

Budding business career

By the mid-1990s, Landry continued to display his trademark hustle, but he focused more on making money than on politics.

He started one business that contracted out maids, and another one that rented airboats. Neither business took off.

Landry left the Sheriff’s Office to work for Southern Tank Testers, which had been founded a few years earlier in Breaux Bridge in St. Martin Parish by a man named Freddie Indest. Landry used his gift of gab to convince clients to hire the company to service their underground storage tanks.

In 1995, he and a high school friend left their jobs with Southern Tank Testers to start their own company, UST Services Group. In the process, they took employees and clients with them, infuriating Indest, according to people who knew Landry then.

Charlene Indest, Freddie’s widow, declined an interview request. Landry said he did nothing wrong.

In 1999, nine years after enrolling, he graduated from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, with a degree in environmental science. He decided to finish school only after an employer offered him a dream job in the pollution insurance industry but withdrew its offer because he lacked a college degree.

Landry that year also began his most important relationship after meeting Sharon LeBlanc one weekend when he went fishing with her father and brother.

Attorney General and Gov.-elect Jeff Landry poses with his wife Sharon Landry in an undated photo. Landry will be sworn in as the 57th governor of Louisiana on Monday, Jan. 8, 2024.

LeBlanc was working as a hospital X-ray technician. Her father Thomas LeBlanc had created a business that sold hand tools at convenience stores. By 2023, Service Tool Co. had become “the leading importer, distributor and merchandiser of hand tools in the United States,” according to its web page.

The relationship between Landry and LeBlanc heated up over time.

“He grew on me,” Sharon Landry said during a recent joint interview. “I was 30. He was 29. We were both single. We just started going to social events together.” She said it might have progressed faster but “he was always in and out, out of town, moving around.”

They married in New Iberia in 2002.

A year earlier, Landry began at Southern University Law School as a part-time student. He had come to see the benefits of having a law degree as a credential and had grown tired of paying lawyers at his tank testing company for work that he thought he could have done.

In 2003, he switched to Loyola Law School in New Orleans and enrolled full-time at the urging of his bride, who told him that he would take forever to finish on a part-time basis. He graduated from Loyola in December 2004, gave up his New Orleans apartment and moved back to New Iberia where the young couple were living.

Landry didn’t plan on taking the bar until Sharon told him otherwise, and the two of them agreed.

"I said, ‘You better start studying right now,’” Sharon said, prompting her husband to burst into laughter. “You did not tell me that information when you wanted to go, when I agreed for you to go."

Landry passed the bar in October 2005, according to bar association records.

Up the political ladder

In 2006, Landry took his most serious step politically by managing Romero’s race to represent the 3rd Congressional District. Romero lost to U.S. Rep. Charlie Melancon.

But Landry benefited by learning the ins and outs of the district and becoming friends with Romero’s biggest donors, especially those in the oil and gas field.

Landry now felt the itch to be the candidate by running to replace Romero, who was term-limited.

To do that, he had to overcome his wife’s opposition.

“You want to know what the funniest thing is?” she asked during the interview. “When we were talking about getting married, getting serious, I gave him a way out. I said, ‘Listen, I know you like politics. My family's not political. We vote.’ But I said, ‘If you ever want to run for office, go find another woman. This is not what I want to do.’ And he said, ‘OK.’"

But: “Look where we are,” she quipped.

In running for Romero’s state Senate seat, Landry faced two better-known state representatives, Sydnie Durand and Troy Hebert. Landry pummeled Durand in the primary, putting him and Hebert in the runoff.

The election pitted two fun-loving Cajuns in what Landry would later call “a bruising race.”

Landry appeared headed to victory when Hebert sent out a mailer in the final days of the campaign that tied his opponent to a 1993 incident where sheriff’s deputies went to a house in St. Martinville with a search warrant looking for drugs.

Landry was living there with several other deputies. In the recent interview, he said he signed the warrant to allow the search, and the deputies found more than 100 grams of cocaine under the house, according to a Houma Courier news story later. Deputies arrested a roommate and long-time friend of Landry’s. The roommate was convicted of stealing cocaine from the evidence room at the sheriff’s department and was sent to prison.

No evidence ever tied Landry to the drugs, said Phil Haney, then an assistant district attorney in St. Martinville and later the district attorney.

But Hebert's mailer — and a robocall by Landry proclaiming his innocence but amplifying the accusation — tainted him enough for Hebert to squeak out a win.

House Speaker John Boehner of Ohio re-enacts the swearing in of then-Rep. Jeff Landry, R-La., as Landry's wife Sharon assists in the ceremony Wednesday, Jan. 5, 2011, on Capitol Hill in Washington. (AP Photo/Susan Walsh) On Monday, Jan. 8, 2024, Landry will become the 57th governor of Louisiana.

In 2010, Melancon gave up his seat to run for the U.S. Senate. Several bigger names passed on the seat, since it would disappear after the next redistricting process because of the state’s slow population growth.

Landry saw it as a steppingstone and ran anyhow.

This time, he positioned himself as a Tea Party candidate who ran hard against President Barack Obama and liberal policies. He won easily.

But two years later, facing U.S. Rep. Charles Boustany, who was better known and well-liked, Landry lost badly.

Then-Attorney General candidate Jeff Landry, right, speaks to the media after signing the papers to officially qualify for the attorney general's race on Sept. 8, 2015. Accompanying Landry are, from left, wife Sharon Landry and son J. T. Landry, then 10. Jeff Landry will be sworn in as the 57th governor of Louisiana on Monday, Jan. 8, 2024.

In 2015, he saw another opportunity, this time by challenging Attorney General Buddy Caldwell, a Democrat-turned-Republican. Landry crushed Caldwell by running as a far-right conservative.

In recent years, Landry has faced questions about business activities.

In 2020, The Times-Picayune | The Advocate reported that a partnership between three labor staffing businesses tied to Landry and a Texas man who was later convicted of visa fraud. That man, Marco Pesquera, said he conspired with Landry, his brother Benjamin, and others to bring hundreds of Mexican welders into the U.S. under false pretenses — and to generate big profits off their labor. The laborers helped build an LNG plant in Cameron Parish.

Benjamin Landry said then that his brother had done nothing wrong and was the victim of a political attack by the newspaper.

In 2023 and 2022, The Times-Picayune | The Advocate reported that Landry funneled money from his campaign and associated super PACs into a staffing company he owns. In all, Landry’s UST Staffing has received $732,039 in these payments since 2011. The arrangement, which is unique among statewide candidates, keeps the public from knowing who Landry paid for his campaign work. His staff has said the payments are entirely legal.

In 2015, Landry earned at least $485,000 from his staffing companies, law firm and consulting company and at least $560,000 in 2016, according to his personal financial disclosure reports.

Landry, his wife and their son, JT Landry, live in a four-bedroom, 6,000-square-foot house in Broussard that they purchased in 2013 for $1.2 million.

The road ahead

Attorney General and Louisiana Gov-elect Jeff Landry stands with Donald Trump in an undated photo.

During his eight years as attorney general, Landry established himself as the leading contender to be governor by championing President Donald Trump’s attacks on liberals, suing to block Gov. John Bel Edwards’ pandemic vaccine mandates, praising the Trump supporters who ransacked the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, suing the Biden administration to allow more oil drilling in the Gulf of Mexico, promising to crack down on crime and telling opponents of Louisiana’s strict anti-abortion law that they could just leave the state.

Since the election, Landry has already flexed his power, getting state lawmakers to choose his preferred candidates to be House speaker and Senate president.

In this file photo, Governor-elect Jeff Landry speaks during a press conference Wednesday, November 15, 2023, at Russo Park in Lafayette, La.

Landry’s critics say that he’ll continue his firebrand tactics as attorney general where he missed few opportunities to win headlines by vilifying people and issues loathed by conservatives. But people who knew Landry during his formative years in St. Martin Parish question that narrative, saying his true nature is to be more moderate.

“He saw that Trump turned people on and wanted to mimic it,” Romero said. “He said to himself: What can I do to make people pay attention to me and think I’m the chosen one”?

In the end, Romero added, “His mom was his guiding light and will always be.”