White roses and lilies stood in for a coffin as drums and hallelujahs filled a shotgun-style church in the 7th Ward. A funeral was underway for Lamar Ford, but his body was 200 miles north in Waterproof, sent ahead to the cemetery.

“They said all the bones in his body were shot up, and nothing they could do for him. They couldn’t fix him up,” said his mother, Pastor Christiana Ford, lamenting the change of plans.

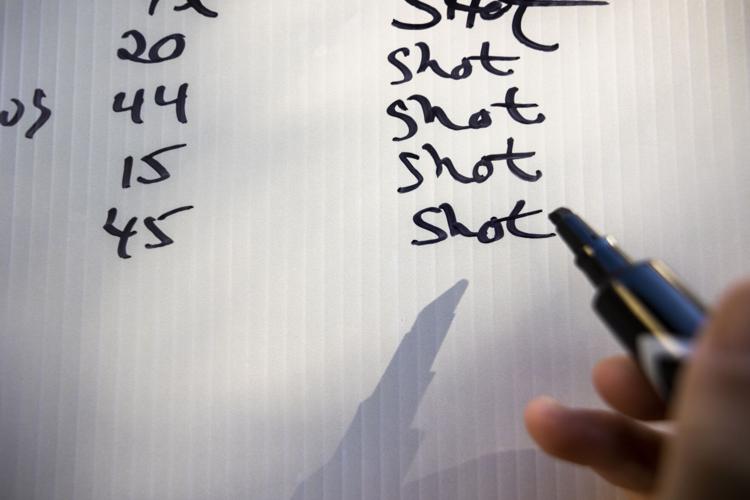

Deacon Luigi Mandile of St. Anna's Episcopal Church in New Orleans adds more names to the long list of people who've died by violence across the New Orleans metro area. This list features just the names from 2022. (Photo by Chris Granger | The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate)

“And then when he hit the ground, the same man got out the car and shot him in the head twice ‘til his brain hit the ground. That’s a hate crime.”

Her 11-year-old grandson shuffled down the aisle, past a photo of a smiling Ford holding him as a baby.

Singer Venessa Holden claps during the funeral for Lamar Anthony Ford at House of Faith in New Orleans, Friday, Aug. 19, 2022. Ford was fatally shot a few stoops down the street from House of Faith where his mother is the pastor and started the Silence the Violence Foundation in 2001. (Photo by Sophia Germer, NOLA.com, The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate) ORG XMIT: BAT2208240839180422

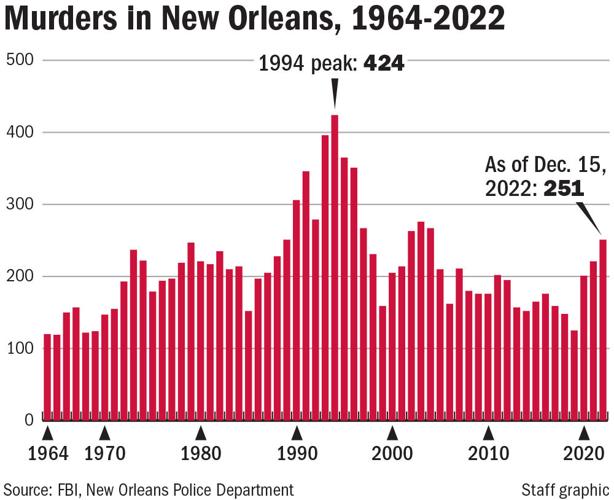

Ford, 39, was in some ways a typical casualty of the type of score-settling violence that has haunted New Orleans this year. Even in a city inured to violence, this has been an extraordinary year: 251 murders so far, a rate of five per week, resulting in what is expected to be America’s highest murder rate.

The rate at which New Orleanians are being killed is the highest it’s been since the ghastly 1990s -- and it comes just three years after the city recorded its lowest rate in a half-century.

Ford was a little older than the Black men aged 15 to 34 who account for nearly half of all murder victims in the city, but Black men in his age bracket make up a growing share of those killed.

In fact, people over 30 account for nearly the entire spike in murders this year, although the number of juvenile victims has also risen, according to NOPD.

The typical murder victim in New Orleans is now a 35-year-old Black man who argues with a younger acquaintance and gets shot with a 9 mm or .40-caliber handgun.

Ford also suffered mental health issues, which crop up in abundance in murders this year, in perpetrators and victims alike. His killing, like most in New Orleans, remains unsolved. Police so far have made arrests in a third of this year’s homicides, a Police Department analysis shows.

Ford used to work as a cook at Pat O’Brien’s before serving eight years for manslaughter over a 2013 slaying in the Lower 9th Ward that prosecutors chalked up to a $40 drug debt. He came home in 2020 and settled into a back room in the house next to his mother’s church on Elysian Fields Avenue.

Ford spent stretches at a state mental hospital while imprisoned, kept bottles of the schizophrenia drug Seroquel and came out talking to voices in his head, his mother said. He would pace around the front stoop, where he sat as a car circled the block about 11 a.m. on Aug. 5.

Christiana Ford said she was out buying doors at Lowe’s when she got the call her son was murdered. What strikes her now is how trouble-free it all seems for the city’s killers.

“It’s easier to get guns, and they’re bloodthirsty,” she said. “But you’re not going to kill a man if you don’t think you can get away with it. Not in the daytime. It’s something bigger we’re not seeing.”

The grim data

Homicides around the U.S. surged with the COVID-19 pandemic but have mostly subsided this year, according to crime analyst Jeff Asher, who works for the City Council. Here, murders kept rising.

Theories abound as to why. Most credit an environment of prevalent guns and fractures – economic, physical and political – from the pandemic; social upheaval over racism in policing; and Hurricane Ida.

But there is no consensus for why shooters remain especially trigger-happy in New Orleans even as the violence has eased elsewhere.

Street justice is one hallmark of the surge in murders in New Orleans in 2022, according to police data and a review of scores of killings, interviews with family members, mental health evaluators and academics.

Spontaneous arguments with friends or acquaintances – squabbles settled with bullets – are another driving force, while old grudges appear to play a role in still other cases.

There are recent signs that the surge in murders may be flattening, even as another man was shot dead Friday night on Old Gentilly Road. New Orleans saw four fewer murders in October and November than over the same period last year, according to NOPD data.

Even so, the city’s murder rate is up 20% this year, rivaled only by St. Louis, Asher projects. And since 2019, the rate is up more than 120%.

“I think we’ll have the most change as far as going from 2019 to 2022 of any city in America,” Asher said. “Very much to be upset about.”

A longstanding problem

New Orleans has long been a city that, more than a crime problem, has a killing problem.

A federal study of murders in New Orleans a dozen years ago noted that the homicide rate in New Orleans then was almost five times higher than in comparable cities with similar overall crime rates.

“What appear to be different about homicides in New Orleans are the circumstances of the events—they are in residential areas and outdoors and do not involve the kinds of drug and gang involvements found in other cities,” the study found. “One is struck by their ordinariness—arguments and disputes that escalate into homicide.”

In 2022, arguments continue to be the most common motive homicide detectives have assigned to about 90 solved cases this year, outpacing retaliation, robbery, drugs or domestic incidents. Detectives attribute 40% of solved homicides since the start of 2021 to arguments.

Who is getting killed, and where, hasn’t changed much as the pace of killing has exploded, NOPD data show. The vast majority of murders involve guns.

At University Medical Center, almost two people a day showed up shot in the first six months of the year, a 27% rise from 2020, hospital data show.

Black people made up 92% of them, in line with previous years. Including those with minor wounds, about one in seven of those patients died, also similar to recent years.

Coroner’s data show that Black males ages 15 to 54 comprise more than three-quarters of the city’s slaying victims. Fewer than one in 10 murder victims in the city is White.

For young Black males, the odds of dying violently on the city’s streets are shockingly high.

About 300 Black males ages 15 to 34 have been slain in the city in three years – representing 1% of their population in the city. At that rate, 1 in every 15 Black men in New Orleans will be murdered by the time he reaches 35.

Even so, the share of murder victims in that cohort has dipped below half of all New Orleans slayings. Making up the difference: older Black men, like Lamar Ford.

If his murder wasn’t vengeance for the crime that sent him to prison, Christiana Ford is at a loss.

“It had to be. He didn’t go nowhere. He’d go to the ice store, the Dollar Store for me. Take people to their homes, come on back,” she said. “It had to come from eight years ago.”

Past is present

Records show several victims of murder this year had been implicated in street violence or gang activity during the last surge in killings in the city, more than a decade ago.

Shot dead at 31 in April on South Claiborne Avenue, Ronnell Owney was among 20 alleged associates of the bloody Central City drug gang 3NG who were convicted of myriad drug crimes and deadly violence.

New Orleans police investigate a fatal shooting on I-10 at the Crowder Blvd. exit in New Orleans East on Tuesday, January 18, 2022. (Photo by Chris Granger | The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate) ORG XMIT: BAT2201191559232051

When the city equaled last year’s murder total in October, the victim was Taivon Aples, 30, who spent years jailed for a slaying outside a Tulane Avenue club in 2008. The case faltered over alleged dirty policing.

Joseph Norah caught a break when District Attorney Jason Williams’ office agreed to toss his non-unanimous conviction and 49-year sentence in a 2010 shooting in the Seventh Ward. Free for just months, Norah died Nov. 16, shot with two others on North Claiborne Avenue.

His murder is one of at least six this year of New Orleans men who had recently been released from state custody, coroner’s and state corrections data show.

Underlying factors

While detectives note the role of longstanding beefs in murders, social scientists point to housing insecurity, isolation, and other stressors, including flagging confidence in police.

“The Black community often sees the police as having abdicated their place in the community. People are on their own,” said Yale University sociologist Elijah Anderson, who has studied inner-city violence for decades.

“Black people know they don’t count in the same way White people count, and people sometimes feel they can murder someone and get away with it. The ‘street cred’ issue is salient. When that happens, you can get hurt over something very simple.”

Mental health troubles also appear to have flourished in many of the city’s killers.

Involuntary psychiatric commitments almost doubled in New Orleans last year, coroner’s records show, from about 2,600 to nearly 4,500 in a year. Figures for 2022 are not available.

The results often show up in eruptions of violence, said Dr. Sarah Deland, a Tulane psychiatrist who has evaluated criminal defendants in New Orleans for 29 years.

“The jails have become very full of mentally ill people,” she said. “I’m seeing more people that are just chronically mentally ill and keep going in and out, in and out on fairly minor charges, or charges that get dropped to fairly minor charges. Next thing you know, something really bad has happened.”

Among those Deland evaluated this year was Jenee Pedesclaux. The 31-year-old mother is accused of stabbing her two children, one fatally, broadcasting the act on social media. She’s now in a mental facility.

New Orleans police investigate a fatal shooting on Interstate 10 in New Orleans on Wednesday, October 20, 2021. (Photo by Chris Granger | The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate)

“A lot of times you feel like you’re watching this in slow motion,” Deland said. “For people that have been in and out of institutions, I’ve sensed a whole lot of, ‘I don’t have what I need to make it in the world now.’”

'I didn't need to ask why'

LaRita Francois points to gentrifying neighborhoods pushing poor residents farther from resources, young shooters who lack “honor among thieves,” and little fear of police in the city.

Francois grew up to parents with addictions and stayed as a teen in a shelter with her mother and younger brother. She now runs Take the Lead Nola, a small nonprofit that provides prison re-entry and other services for disabled people,

She moved from the city to escape the violence, she said. Her brother, Ferdinand Francois III, did not.

He played point guard for the Louisiana Dribblers, a traveling youth basketball team, before sliding into crime and pills, she said. He went to prison, then rehab, and suffered from depression that he ignored.

“I think he was afraid to say something,” she said. “The mental health system does not make it easy to trust.”

Ferdinand had filed papers in August to start a business, JFF Auto Sales. But he was living with a girlfriend in an apartment on the city’s deadliest block, at the foot of the Danziger Bridge on Chef Menteur Highway. Seven people have been killed there this year in six incidents. All seven were Black. Six were shot dead.

Ferdinand was among them, shot Oct. 26 in a case the coroner ruled a homicide.

LaRita Francois said police recovered a dozen shell casings.

“The funeral home asked for a hat,” she said. “I didn’t need to ask why.”

Staff writer Jeff Adelson contributed to this story.