Michael Cerveris, who splits his time between New Orleans and New York, made his Broadway debut 30 years ago by originating the title role of “The Who’s Tommy.” To prepare him for the role, The Who's Pete Townshend coached him on how to be a rock star.

Cerveris has since won two Tony Awards for best actor in a musical. His TV credits include “The Good Wife,” “The Blacklist,” “Treme” and the Fox sci-fi series “Fringe,” on which he played an Observer named September.

From 3 p.m. to 8 p.m. Sunday, Oct. 22, Loose Cattle, the Americana band he co-founded with singer Kimberly Kaye, hosts “Stampede! Deux” at the outdoor Broadside. The bill includes Lydia Loveless, Jay Gonzalez of the Drive-By Truckers, pianist and songwriter Lilli Lewis and guitarist/songwriter Dave Jordan.

The following interview with Cerveris, edited for clarity and length, is taken from this week’s episode of “Let’s Talk with Keith Spera” on WLAE-TV.

The New Orleans-based Americana band Loose Cattle features, from left, violinist Rurik Nunan, guitarist Michael Cerveris, singer Kimberly Kaye, bassist Rene Coman (standing) and drummer Doug Garrison.

You’re a member of the Screen Actors Guild/American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, which is on strike. While on strike, the union prohibits its members from talking about their past TV and movie work. Why?

That work is still out there being streamed and popping up on different networks. People, and to some extent the studios, may not realize how much actors contribute to promotion. It can be as big as going on a press junket or as seemingly trivial as posting things on Instagram.

So the idea from the union is that we are not going to help further the income or awareness of work that was done under (the union’s old) contract (with studios and producers).

And the very big issue of AI and its place in our industry needs to be addressed now.

Has the strike cost you work?

I haven’t worked since December 2022. A show that I was doing (“The Gilded Age”) had finished the second season and, in theory, we would have been back to work. That is not happening. And (neither are) any number of things that I would have at least been auditioning for.

The way streaming entities put "content" out — although I hate using that term — is so different from the original model of the networks. It was a seasonal thing: You did 26 episodes; it started and finished at the same time. You could count on when you’d have hiatus time in between.

Streaming undid all of that because they put shows on whenever they feel like it. It can be maddeningly long between seasons. That means that what seems like a really good paycheck has to last you for a couple of years sometimes, because you’re on hold. You’re obligated to be available, so you’re limited in what other work you can do.

You studied theater at Yale.

When I was there, Yale didn’t consider the theater to be a sufficiently academic discipline, so there wasn’t a major in the theater. My degree is in the humanities with an emphasis in theater studies.

I wasn’t entirely certain that was what I wanted to do with my life. I’d grown up as the son of parents who had met at Juilliard; my dad was a pianist and my mom was a modern dancer. They both chose not to have performing careers; they went into academia. So I had a healthy regard for the challenges of a life as a performer.

I had more interests and things to explore. I explored all of those through my four years at Yale. At the end of it, I came to the realization that I didn’t have any greater aptitude or interest in anything else. So I thought I’d go to New York (to act) and see how it goes.

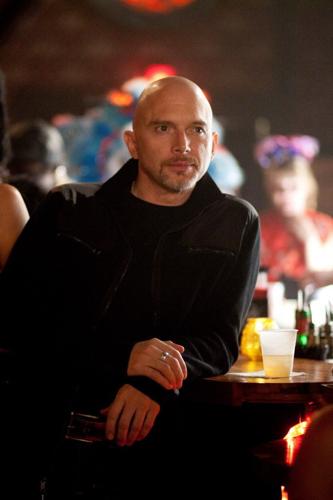

Michael Cerveris and Lucia Micarellil are shown in a scene from the third season of the HBO series "Treme." He played the music manager Marvin Frey; Annie T. (Micarelli) was one of his clients.

My career since then has basically been getting almost to the edge of leaving the business any number of times, basically thinking every job is my last job, but never quite giving up altogether.

What do you remember about preparing for your 1993 Broadway debut as Tommy, from The Who’s rock opera?

For the audition, there was no script. It sounded like it could be a disastrously bad idea to do a stage musical version of The Who’s “Tommy.” It’s like one step away from “Tommy on Ice.”

I auditioned by singing and playing David Bowie’s “Young Americans,” but I didn’t know what role I was auditioning for. It was well into the process before I realized they were considering me for Tommy.

Pete Townshend wasn’t at the La Jolla Playhouse (in San Diego, where the show premiered) for the rehearsal process. I remember very vividly the first time we were going to be singing with the full band, his flight was delayed. I was more than a little anxious.

The first thing I sang was “Amazing Journey” about 15 minutes into the show. By that time, I’d kind of forgot that he was coming. Right as I step up to the microphone, the doors of this aircraft hangar rehearsal room open and the light comes streaming in behind this tall figure of one of the gods of rock 'n’ roll. I had to sing “Amazing Journey” as Pete Townshend’s entrance music, basically. After that, I figured I could handle anything.

Before the show moved from San Diego to Broadway’s St. James Theatre, you had to re-audition.

I had a disastrously bad re-audition, after having done the part 110 times. I had the flu right before the audition. Then I warmed up in the music director’s apartment, who had a bunch of cats, and I’m allergic to cats.

I lost my voice entirely in the middle of the audition. It was all my nightmares coming true, after months of anticipating my big chance.

The director and Townshend then took you to dinner.

I thought it was my consolation dinner. At some point, Pete says, “I want to bring you to London, and spend some time with you in my studio, and introduce you to guys I grew up with when ‘Tommy’ was being written and show you where The Who played our first gigs.”

I was thinking, “This is a pretty great consolation prize.” My first clue that I was actually going to be on Broadway wasn’t until he said, “We saw more than a thousand guys for the role of Tommy and we’re going to give the part to the guy who gave the absolute worst audition of all of them.”

And I did get to go to London and do all that with Pete. He said, “I can’t teach you how to act, but I can teach you how to be a rock star.” So I got rock star coaching from Pete Townshend.

In this image released by The O and M Company, Michael Cerveris appears in a scene from "Fun Home," a musical based on Alison Bechdel's graphic novel memoir. The show was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Drama (Joan Marcus/The O and M Company via AP).

A few years later, you won your first Tony Award for playing John Wilkes Booth in “Assassins.” You’ve also played the murderous Sweeney Todd and the intense Hedwig of “Hedwig & the Angry Inch.”

I seem to specialize in dark characters. I don’t know if it’s something I put out there in the world, or I work out all my aggressions in that.

Since I was little, I always was fascinated by the monsters in stories and always sided with the monsters. I always felt like Frankenstein didn’t ask to be stitched together. King Kong didn’t ask to be dragged off the island where he was perfectly happy.

I always saw things from the monster’s side and that’s essentially what the actor’s job is: to find your character’s point of view. When you’re playing John Wilkes Booth, you argue the truth from his eyes. When you have such brilliant writers as Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman, you can invest yourself fully in trying to explain the world from that character’s point of view and trust that it’s not going to be misconstrued or misappropriated.

Nobody believes they’re the villain. Everybody believes they’re the hero of their story and their actions are justified for whatever complicated and sometimes completely misguided reasons.

That’s where I maybe invest a little more heart and humanity into these people. Not trying to mask their evil choices but to try to argue that we’re not so different from them. If we want to progress as people, we need to recognize that we share that humanity, and then figure out what went wrong.

A decade after winning your first Tony, you won again in 2015 for playing the closeted gay father in “Fun Home,” a musical based on cartoonist Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoir.

I had been nominated for “Tommy” and didn’t win. That was kind of a blessing. I went through the fun and anxiousness of that whole process, but then immediately had it put back in perspective. I didn’t win, and my life didn’t change; I still was doing a great job that I loved doing. My focus was put back on the thing that really matters the most: the work itself.

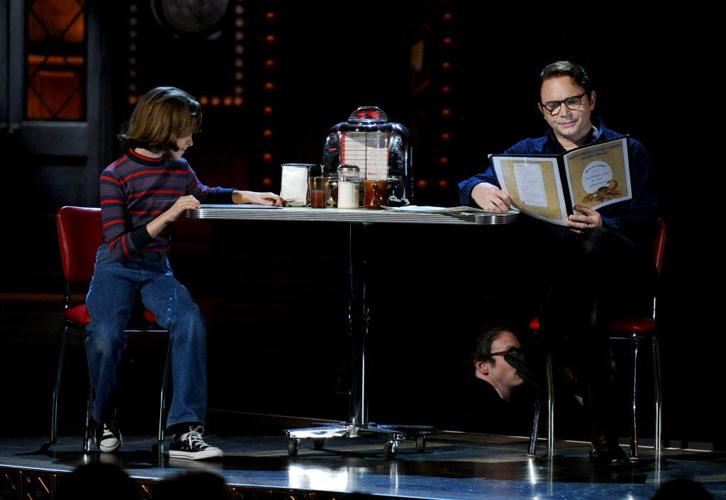

Sydney Lucas, left and Michael Cerveris of the cast of "Fun Home" performs at the 69th annual Tony Awards at Radio City Music Hall on Sunday, June 7, 2015, in New York.

The next time I was nominated, for “Assassins,” I went into it with a much different headspace. My expectations were a lot lower: I know what it’s like to lose, so if that’s what happens, I can do that, and I’ll still have a good time.

I was nominated with a friend of mine named Michael McElroy. I kept reminding myself, “Do not stand up if you just hear ‘Michael,’ because it might not be you and that would really be embarrassing.”

So when I won, it was kind of a surprise and really disorienting.

Michael Cerveris, left, and Kimberly Kaye front the country/Americana band Loose Cattle.

What was the original concept for the band Loose Cattle?

I’ve always had such a specific idea of what a musician is from my dad. He’s been retired for years and is in his 80s, but he still practices and plays piano several hours a day.

That kind of dedication, mastery of the instrument and knowledge of theory, I don’t have. I still don’t really read music. I’m a self-taught musician. I basically just put myself in a room with real musicians and lower them to my degree of ability.

(Singer) Kimberly (Kaye) was in a bunch of punk and ska bands in New Jersey, where she grew up. I played guitar with Bob Mould (of alternative band Hüsker Dü) and have always been a rock 'n’ roll guy.

Kimberly and I were dating at the time and somehow thought, “Having a band with your partner is a good way to get along better.” The relationship ended and we figured out that we were much better suited to be just musical partners and very best friends.

We started Loose Cattle with no expectations. We thought we’d do covers and play in people’s living rooms and do country stuff because I come from West Virginia. It’ll just be fun; we’ll never rehearse.

But pretty quickly we got chances to play on “Mountain Stage” on NPR and Lincoln Center’s “American Songbook” series. The kinds of things you work toward for years as a band were falling in our laps. We’re like, “Maybe we should rehearse and take it more seriously.”

“Let’s Talk with Keith Spera” is a partnership between WLAE-TV and The Times-Picayune | NOLA.com. It airs Thursdays at 7:30 p.m., with repeats on Sundays at 9:30 p.m. (Channel 32 in New Orleans, COX Channel 14 and 1014, Spectrum Channel 11 and 711 and AT&T and DISH Channel 32). Episodes are also available on the WLAE YouTube channel.