Highways these days are supposed to convey you long distances at steady speeds, without much twisting and turning, right? After all, as the author J.R. Rim once wrote: “No road is straight until you hit the highway.”

Clearly Rim never drove through Harahan. It is there that an S-curve forces 40 mph drivers to slow down — twice in the space of 1,320 feet — if they wish to continue on the four-lane Louisiana 48.

What’s up with that, wondered Jim Copolich of Destrehan, who asked Curious Louisiana about Harahan's two “very sharp 90-degree turns” on Jefferson Highway. “There must have been a very good reason to have turns like this in a major thoroughfare.” (There's a similar S-curve downriver in Old Jefferson, between Ochsner Medical Center and New Orleans, but that's another story for another day.)

The short (TL;DR) answer to Copolich’s question is the railroad. Two railroads, in fact.

First, however, it might be instructive to detour into the history of United States highways in general and Harahan in particular.

Key point: Highways as we know them in the 21st century were not planned and built end to end by the government. In most cases, they grew from short, disparate, unconnected and unpaved paths — first for pedestrians, later for horses and wagons — through the woods, prairies, marshes, plains and mountains of the country.

The Mississippi River bends through Jefferson Parish in a map from 1891, before Jefferson Highway was built. The blue marker notes the present location of Harahan City Hall.

It was only with the advent of the automobile at the turn of the 20th century that these paths came to be connected over distances and made into “rock roads,” that is, graveled.

Even then, it wasn’t the state or federal government that made it happen. Instead, it was titans of commerce and local civic boosters who saw the potential of the automobile and began clamoring to link, improve and extend the muddy tracks they had inherited. They formed highway associations, sold memberships to raise money for the work and catenated local and country roads into interstate routes.

Thus came to be Lincoln Highway (New York-San Francisco), Dixie Highway (Mackinaw City, Michigan-Miami) and Pacific Highway (Blaine, Washington-San Diego).

And, between Winnipeg, Manitoba, and New Orleans, where its southern terminus is marked on a granite block at the intersection of St. Charles Avenue and Common Street: the 2,373-mile Jefferson Highway. It was named for the third U.S. president and architect of the Louisiana Purchase, and known informally as the Palm to Pine Highway.

The Jefferson Highway logo is seen in an undated photo on a utility pole in Lamoni, Iowa.

The Jefferson Highway Association hosted its first convention in New Orleans in November 1915, with more than 300 delegates vying to determine the route between Winnipeg and New Orleans. Over the next 11 years, members completed the fieldwork and blazed the route with signs: a vertical rectangle divided into three bars, blue at the top and bottom and the letters JH in black on a white field in the middle.

In what is now Harahan, however, it wasn’t remote dirt paths that were subsumed into Jefferson Highway. The lanes were built on either side of the privately owned Orleans-Kenner Electric Railway, which had gone under construction March 19, 1914, and started service Feb. 25, 1915 — and already had an S-curve in Harahan.

That’s because an even bigger railroad was in the way of the O-K.

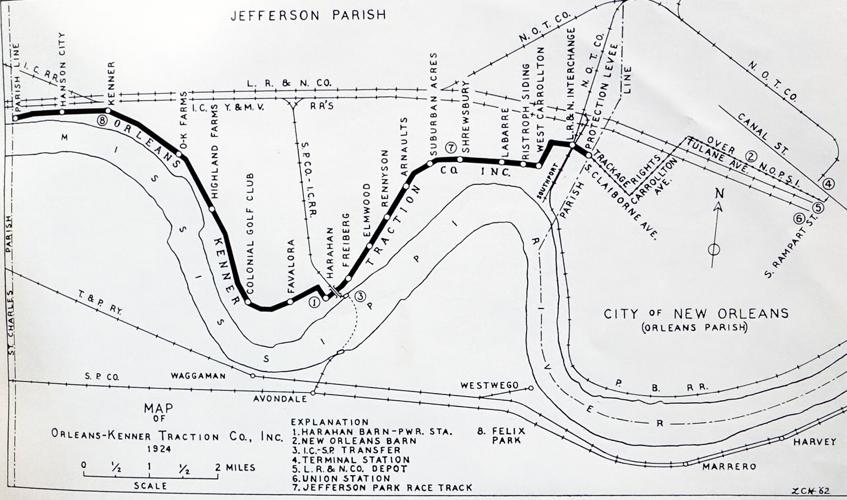

The 1924 route of the Orleans-Kenner railway route is seen in a 1962 map by Louis C. Hennick.

In 1894, Illinois Central Railroad had built a large, multi-track repair yard on the former Lafreniere Plantation, between what is now Al Davis Road and Sams Avenue in Elmwood. Twenty years later, the railroad also bought the long, narrow property between its yard and the future Harahan. This was a 100-acre tract where Southern University had operated an experimental farm for its agriculture students, and the railroad made it into a town of sorts for its 1,800 local workers.

By tracing an S-curve, the O-K line avoided crossing Illinois Central’s company town and big repair yard.

It did have to get past one IC track. That one connected the yard to the Southern Pacific Railroad ferry landing, where trains arriving from the Midwest and East Coast were barged across the Mississippi River to Avondale, to continue their westerly route across the country. The track to the ferry was elevated 30 feet to get over the river levee, so the O-K line ran beneath it.

Much has changed since then. Southern University moved from its original location in New Orleans to Baton Rouge in 1913. The O-K line ceased operations in 1930, victim of the exploding popularity of automobiles. The rail ferry across the river became obsolete when the Huey P. Long Bridge opened in 1935. The tracks of the IC repair yard were gradually abandoned and pulled up by 2012, and the Illinois Central was sold in 1998 to the Canadian National Railway.

Harahan, meanwhile, had been incorporated in 1920. It is named for James T. Harahan, president of the Illinois Central from 1906 to 1911, whose company is largely responsible for Jefferson Highway having that S-curve today.

SOURCES: Richard Skoien and Daniel Gitlin, Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development; Richard Campanella, Tulane University School of Architecture; The Times-Picayune archives; Roger Bell, Jefferson Highway Association; “Louisiana: Its Street and Interurban Railways” by Louis C. Hennick and E. Harper Charlton (Shreveport: Louis C. Hennick, 1962); U.S. Geological Survey; Archives, Manuscripts and Rare Books Department, John B. Cade Library, Southern University and A&M College; Bryan Wallace, city of Harahan; “Southern University's Agriculture and Mechanical Departments: Descriptive Analysis of the New Orleans Years, 1880-1913" by Charles Vincent (Agriculture and Human Values, Vol. 9, 1992); “Harahan History” by Ned Hémard, (New Orleans: New Orleans Bar Association, 2009); “O-K Rail Line, Kenner to New Orleans” by Jeremy Deubler, The Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies, University of New Orleans.