The question of where Mardi Gras began pops up again and again among those curious about Louisiana culture. We'd be delighted to report that the first North American Carnival celebration definitely took place in New Orleans.

The trouble is, Mobile has a somewhat convincing claim to being the cradle of Mardi Gras, too. It all comes down to whether you believe a New Year's Day parade can be called a Carnival parade.

Carnival, the pre-Lenten “farewell to meat” festival, goes back hundreds of years in Catholic Europe. The tradition came to the New World with various colonists.

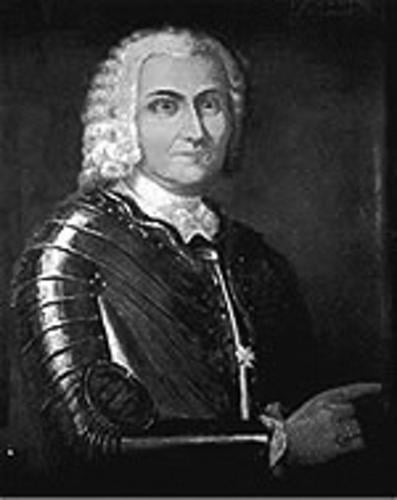

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville French explorer who, with his brother, Pierre LeMoyne, Sieur d'Iberville first commemorated Mardi Gras near what's now New Orleans

The first mention of Mardi Gras

The French-Canadian explorer Iberville noted in his journal that he and his little brother Bienville spent Mardi Gras 1699 resting on the bank of the Mississippi River before paddling onward to Baton Rouge. But it doesn’t sound like they partied it up much.

There’s no mention of light-up beads, Popeye’s fried chicken, king cake vodka or the 610 Stompers. Nonetheless, Iberville dubbed their muddy stopping spot Mardi Gras Point.

So, for the next three centuries, we in New Orleans clung to that fact whenever attempting to validate our claim as the birthplace of Mardi Gras. But it’s a stretch. Not only did Iberville and Bienville not celebrate, they weren’t in New Orleans. They were 66 miles south of Canal Street, across the river from Triumph, Louisiana. If there had been a Triumph, Louisiana, or a Canal Street, or a New Orleans for that matter.

Bienville didn’t found New Orleans until 19 years later, in 1718. He’d helped found Mobile way before that, in 1702.

The Beauf Gras float from the Rex parade smokes its way down St. Charles Avenue in 2013.

Papiér-maché BS (bull sculpture)

If you Google the topic of Mardi Gras in Mobile, you will discover that there may have been a Mardi Gras observance in the settlement just one year after it was founded, in 1703.

By 1711, some say there was already a small Carnival parade in Mobile, featuring a float decorated with a papiér-maché bull, that rolled along the main street. This is sometimes touted as the first Mardi Gras parade on the continent.

But, according to Cartledge Blackwell, the curator of the Mobile Carnival Museum, these collective memories of 18th-century Carnival occurrences should be taken with a grain of salt, since they can’t be confirmed by any documentation. As Blackwell put it, “there’s no journal, no newspaper, no firm histories.”

A group of cows take part in the Bourbon Street Awards hosted by drag queens Bianca Del Rio and Varla Jean Merman on St. Ann Street on Mardi Gras, Fat Tuesday, in New Orleans, La. Tuesday, Feb., 2017. The Krewe of Armeinius strives to preserve the culture and events of Gay Mardi Gras.

What's a Cowbellion?

According to Blackwell, it wasn’t until 1831 that a well-documented public celebration popped up in Mobile that is considered (by some) to be a version of Carnival.

History recalls a Pennsylvania-born cotton broker named Michael Krafft, who founded a tongue-in-cheek club called the “Cowbellion de Rakin Society” that established an annual dawn parade. Like a "Saturday Night Live" sketch, as they marched, the gaggle of young dudes clanged rakes and other farm implements, plus cowbells — and more cowbells. Which doubtlessly annoyed, but also amused, the growing town by the bay. In the next 10 years, Krafft’s society added floats and themes to their noisy procession, which, Blackwell said, made the Cowbellion parade the model for Carnival parades to come.

But here’s the thing. Krafft’s processions always took place on New Year's Day. Which leads some to disqualify them as the first bona fide Carnival parades. After all, traditionally, Carnival doesn’t commence until five days later, on King’s Day, Jan. 6.

Question: Do the folks in Mobile also consider Halloween to be Thanksgiving?

A champagne toast is exchanged by Comus, god of festive joy and mirth, and his queen as the Krewe of Comus parade halted before the Louisiana Club on St. Charles on Fat Tuesday 1955. (Photo by A.P. Vidacovich/The Times-Picayune archive)

Borrowing a parade

Anyway, for the people of New Orleans, it was a good thing that the Cowbellions paraded several weeks before Fat Tuesday. In 1857, six former Cowbellions who’d relocated to New Orleans decided to form a similar parade in their adopted home. The young men called the new club Comus, after the Greek demigod of drunken partying.

As New Orleans Mardi Gras maven Arthur Hardy wrote, “Comus borrowed the floats and costumes that had been used in the Mobile group’s New Year’s Eve parade 55 days earlier.”

Somewhere along the line, the Cowbellions had begun adopting annual themes. Hardy said the theme of the 1857 Cowbellians parade in Mobile was "Pandemonium Unveiled." The somewhat related theme of the first Comus parade and ball was "Demon Actors" from Milton’s "Paradise Lost."

The borrowed parade was a big success, and thus the prototype of the float parades that now swell the Crescent City streets each winter was imported from 144 miles east. No doubt.

But Comus wasn’t New Orleans’ first Mardi Gras parade. Nope.

In fact, back in 1857, some hoped that the new, more refined Comus parade would help stifle the rowdier, costumed foot parade that had been taking place annually in the French Quarter on Mardi Gras morning for at least 20 years.

Members and friends of the Societe de Saint Anne, parade through New Orleans neighborhoods on Mardi Gras, February 28, 2017. The Society was founded in 1969. Known for the very elaborate and beautiful costumes of its members, the core group gathers in the Bywater neighborhood of New Orleans each Mardi Gras morning, with the Storyville Stompers brass band providing the music. As they pass through the Faubourg Marigny and French Quarter, additional costumed marchers join the parade at various coffee-shops and bars along the route. (Photo by David Grunfeld, NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune)

Bona Fide Mardi Gras parade

The Feb. 28, 1838 Daily Picayune reported that “yesterday was a jolly time in our city. The grand cavalcade which passed through the principal streets was an entertaining sight — being remarkable for numbers, for the splendor of their equipage, and the ludicrous effect which they produced.”

The unnamed reporter goes on to say that Mardi Gras is a day “honored with great pomp and circumstance, because it is the end of the Carnival” when “all masquerades, balls and other public amusements cease.”

As the Carnival reporter described it, “in the procession were several carriages, superbly ornamented — bands of knights, cavaliers, heroes, demigods, chanieleers, punchinellos, and etc.”

“The crowd, which preceded, accompanied and followed them, was like a vast river. We have never seen exactly such a throng.”

Even the most staunch supporter of the Mobilian Mardi Gras genesis story would have to agree that the wording of the 1838 account of a Mardi Gras parade in New Orleans suggested that the festival wasn’t new.

In fact, time and again online, we’ve found references to the date 1827, as the big bang moment for New Orleans Mardi Gras. The History Channel website states that “On February 27, 1827, a group of masked and costumed students danced through the streets of New Orleans, Louisiana, marking the beginning of the city’s famous Mardi Gras celebrations.”

But, to be fair, a gaggle of dancing students doesn't necessarily constitute a parade, and the History Channel doesn’t cite the source of the factoid, anyway.

Cowbellions-Shmowbellions

So, let's climb into our time machine again and travel back almost 100 more years, to meet a group of bored bons vivants in La Nouvelle-Orléans, who decided to celebrate Luni Gras 1730 by crashing a dance party.

One of the dudes dressed as the Marquis de Carnival, in a gold-trimmed suit. Other men cross-dressed as Amazons in red clothing, and one costumed as a shepherdess, with beauty marks aplenty. As they promenaded toward the party, they were accompanied by a violinist, an oboist, and eight enslaved men lighting the way with flambeaux.

Somewhere along their trek, probably on what's now Bayou Road, between the French Quarter and Bayou St. John, the group of maskers was scattered by a group of large bears that were apparently also out celebrating Carnival. This was all recorded in the journal of Marc-Antoine Caillot – the shepherdess -- which you can read all about in the book titled "A Company Man: The Remarkable French-Atlantic Voyage of a Clerk for the Company of the Indies."

Present us with flambeaux-lit costumers, accompanied by musicians wandering around on the night before Mardi Gras, and we in the 504 will call it a Carnival parade, y'all. Maybe it's an itty-bitty Carnival parade, but it's a Carnival parade, about a century before the Cowbellions-Shmowbellions.

Friendly rivalry

A parade rider throws beads on Joe Cain Day during Mardi Gras in Mobile, Ala., Sunday, Feb. 27, 2022. Joe Cain Day, named for a clerk who started Mobile's modern Mardi Gras by dressing up and parading through town in the late 1860s after the Civil War, roared back to life after taking a year off because of the pandemic. (AP Photo/Jay Reeves)

Irrefutable evidence aside, the rivalry over which city was the birthplace of the big party is perennial. In 2018, the Alabama Tourism Department placed billboards in Louisiana with messages such as, "You are 114 miles from America's Original Mardi Gras.”

But the Mobile Carnival Museum's gentlemanly Mr. Blackwell said most Mobilians aren’t really competitive about it.

They’re delighted “that a creation from Mobile has gone to New Orleans,” he said. “Both cities have contributed to the flowering of Carnival.”

Note, if anyone can provide the exact newspaper reference or journal entry that describes the 1831 Cowbellions parade, we would include quotes in this story. Sent to dmaccash@theadvocate.com.