For Stephan Pastis, the idea for his new middle-grade novel "Looking Up" showed up one day in the Faubourg Marigny when he looked across the street and didn’t like what he saw.

Pastis, a California native and the cartoonist behind the nationally syndicated comic strip “Pearls Before Swine,” has been a regular visitor to New Orleans since he was a 17-year-old son of Greek immigrants in town for an American Hellenic Educational Progressive Association convention. In the nearly 30 years since then, he’s returned dozens of times, often for weeks at a time to work on writing projects.

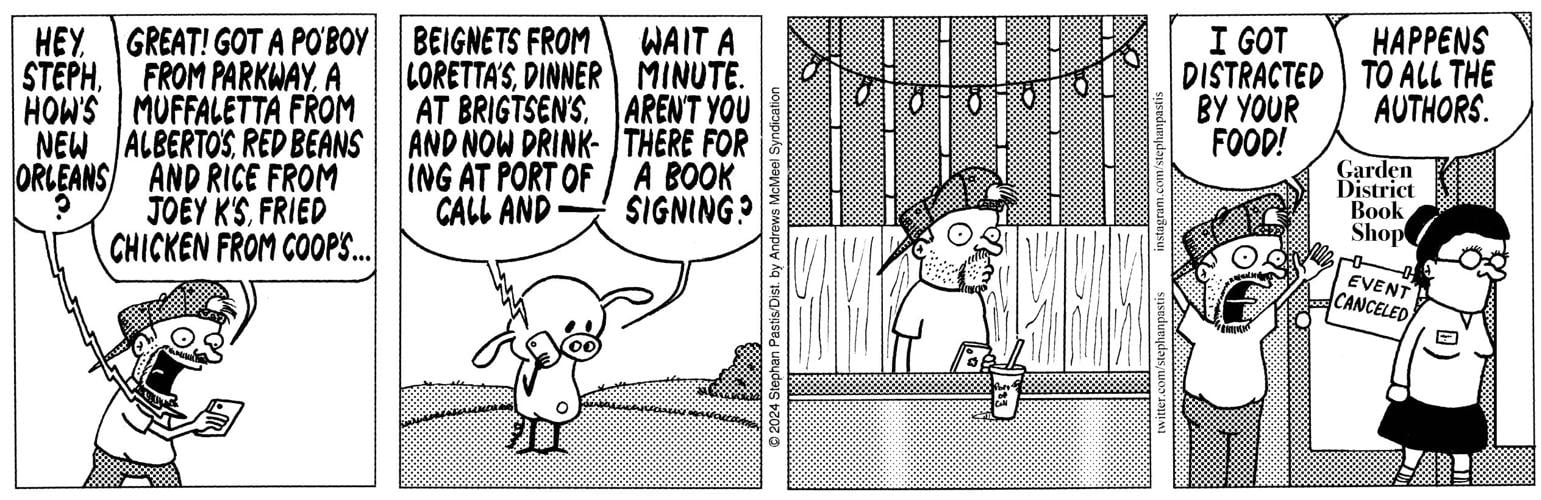

“I’d discipline myself to write until noon because then the sandwiches call your name,” he says, checking off his favorite po-boy shops and watering holes and music clubs. “It’s just so difficult to not get that first drink at one o’clock in some courtyard.”

On another trip, he visited Tulane University to dig up John Kennedy Toole’s early Tulane Hullabaloo cartoons. Pastis will hold forth on "A Confederacy of Dunces" for as long as you’ll let him. He considers it a perfect comedy (“Ninety-eight percent pure gold, as close as you can get”) and is quick to advance his belief that the novel’s ending represented Toole’s reworking of the last scene of "A Streetcar Named Desire" (unlike Blanche DuBois, Ignatius J. Reilly escapes).

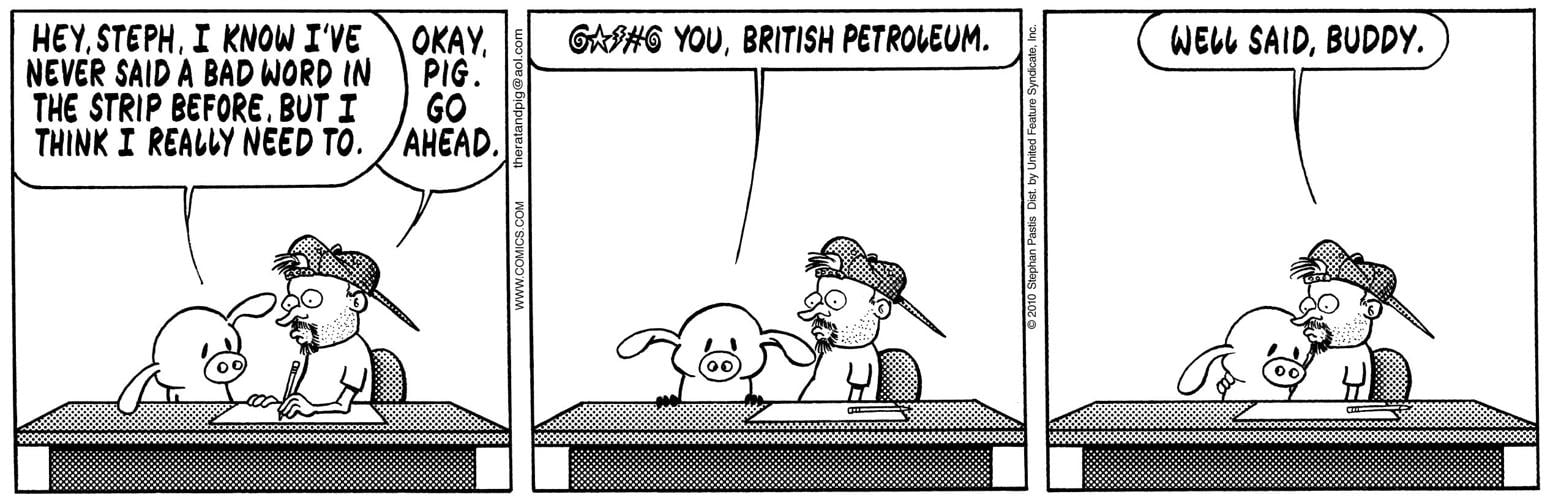

Pastis’ passion for the city has occasionally found its way into “Pearls Before Swine,” now in its 22nd year and appearing in some 800 newspapers, including The Times-Picayune.

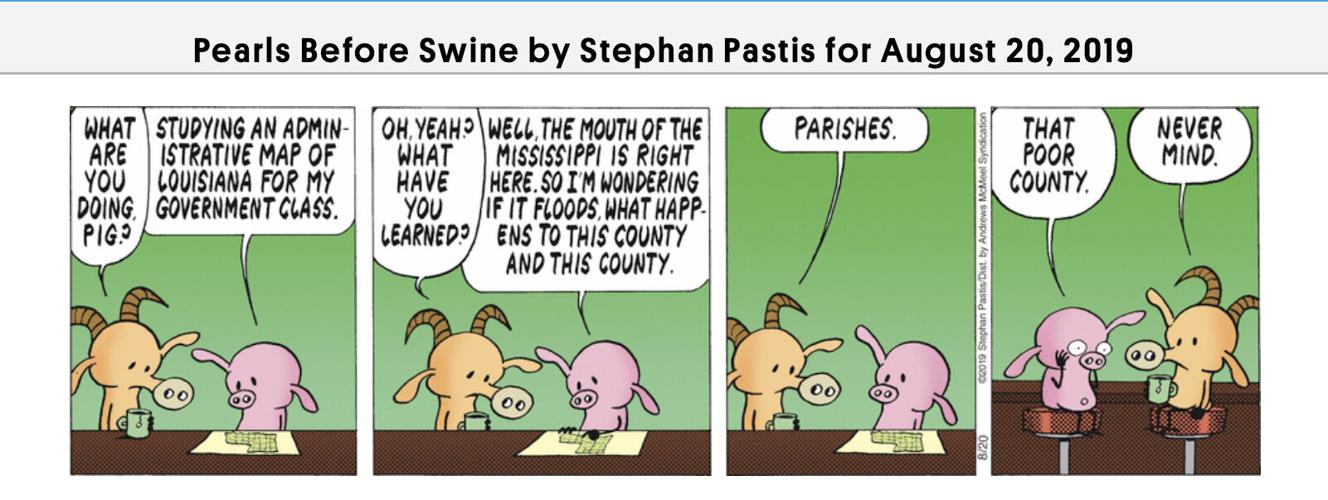

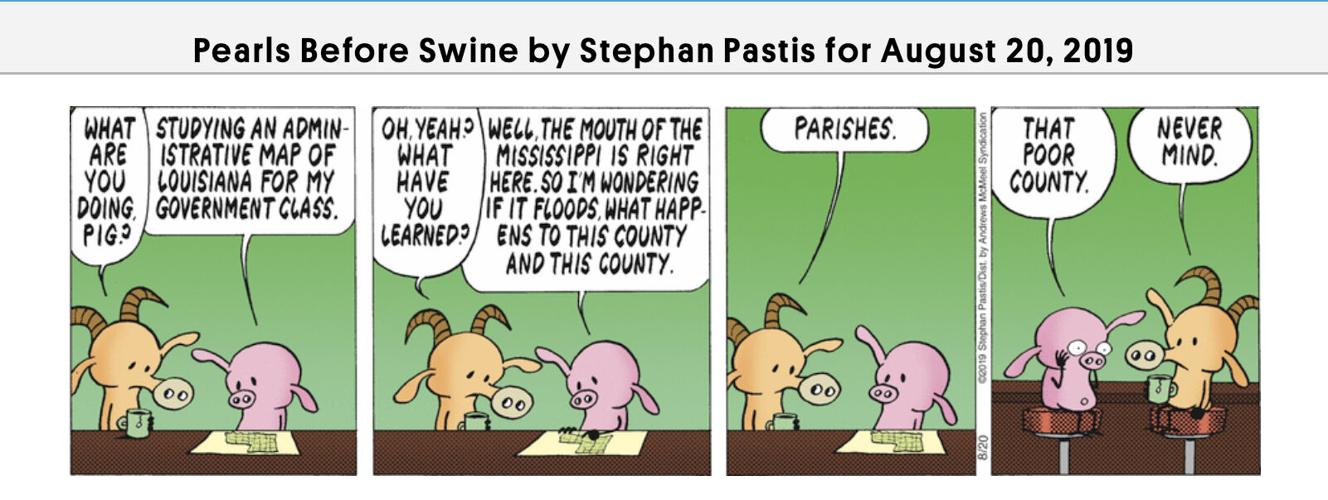

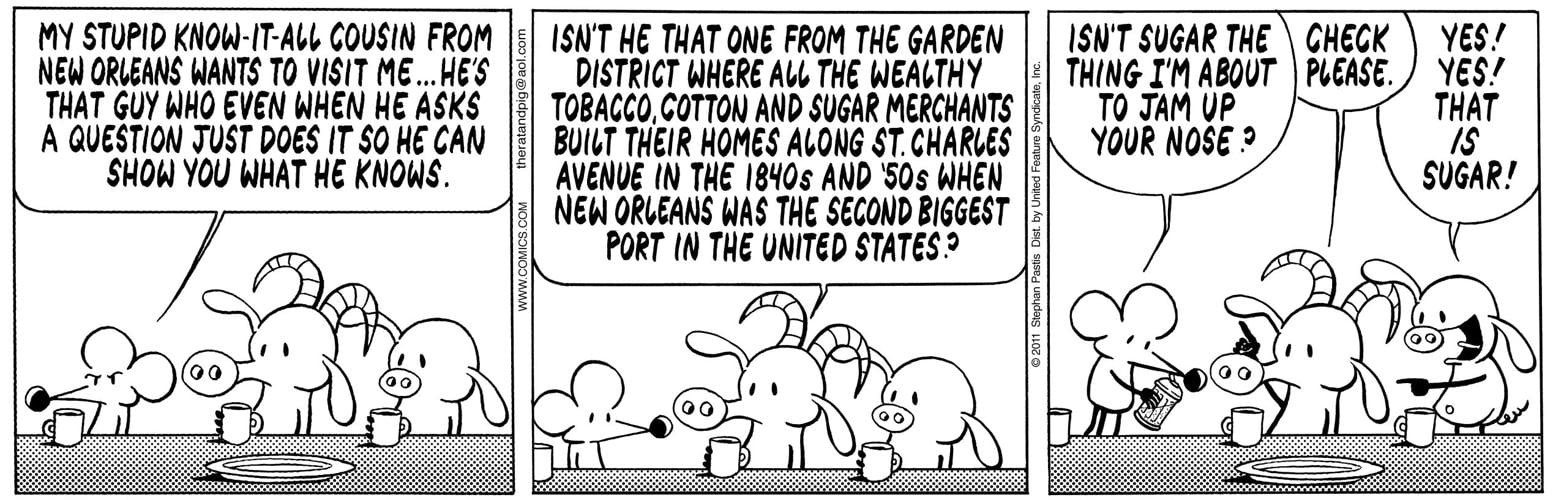

In one strip, the character Rat has a know-it-all cousin from New Orleans. In another, Pastis uses his animal characters to offer a pun about counties and parishes that is both comic and poignant:

Pig (looking at map): “I’m wondering if it floods, what happens to this county and this county.”

Goat: “Parishes.”

Pig (sadly): “That poor county.”

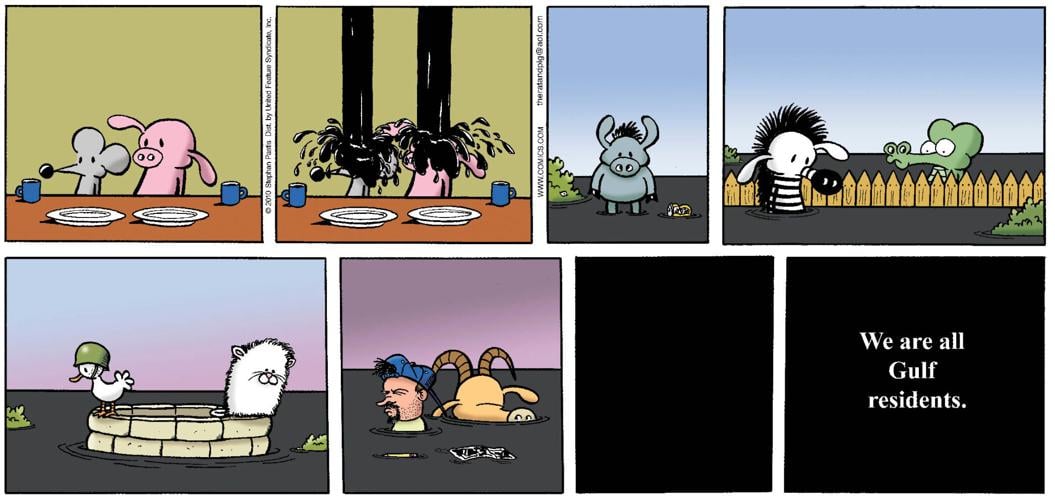

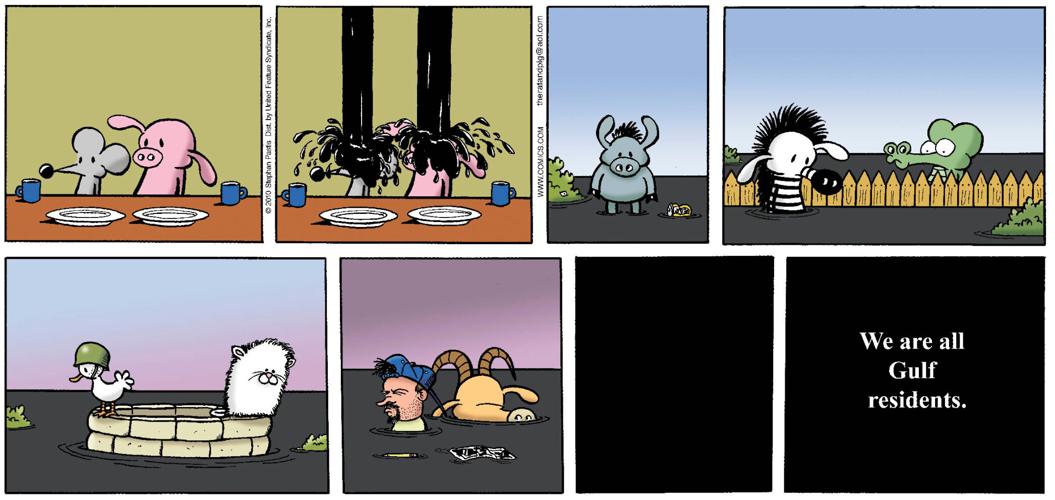

During the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, Pastis, in an unusually raw and political moment for both him and his strip, dispensed with gags altogether. Instead, he showed all his characters — himself included — drowning in oil. “We are all Gulf residents,” that comic concluded.

Remembers Pastis: “I was just so enraged.”

On this day in the Marigny, Pastis experienced another revelation that called for a response. He realized that on each successive visit to New Orleans, he was seeing the city gentrify in real-time.

“I’m now staring across the street at people who look like me,” he says. And as someone who had always preferred to stay in neighborhood Airbnbs, he figured that he could be part of the problem.

This led to the birth of Saint, the young heroine of "Looking Up," who rails against the wrecking ball’s destruction of all she loves, including her favorite toy store and her best friend’s house. Saint’s city isn’t named, but words like “krewe” and descriptions of Spanish moss — and, of course, Saint’s name — don’t exactly make it a mystery.

“I put in lots of clues. I know gentrification is happening in other places, but New Orleans is where I saw it. In recent years, you see people just buying up the shotguns,” Pastis says. “You lose the people, you lose the city. Then it becomes Venice. It becomes a film set.”

Saint’s battle might be called Quixotic — or Ignatiusian, for Saint seems to have inherited her DNA from Pastis’ favorite comic character.

Like Ignatius, she spends much of the book dressed in costume. She adopts the language of antiquity and thunders against modernity, saying, “The past was the place I liked best.”

And as with Ignatius, her first foil is her mother — in Saint’s case, a real estate agent whose office is handling the very property transfers that are driving Saint to despair.

And like Toole’s book, "Looking Up" is very funny.

Yet it’s a humor that, as with “Pearls Before Swine,” can be bittersweet. Indeed, the major theme of "Looking Up" is loss.

Pastis says that’s another reason why he set it in New Orleans. “Death is all around you in New Orleans, uniquely so,” Pastis says. “It’s the one city in the United States where you really feel the presence of those who are gone.”

Disney adapted Pastis’ previous book series, Timmy Failure, into a feature movie that originally was set to film in Louisiana.

Pastis says that insurance costs for a September shoot eventually resulted in a change of locations. He hopes he’ll get a second chance to return to New Orleans for a movie based on "Looking Up."

If so, he has his personal checklist of stops ready. Says Pastis: “If you walk away from New Orleans and you say that city is boring, that says more about you than it does about New Orleans.”