The road to Cocodrie is one Donald Boesch knows well, from his old house in Houma all the way down to the ragged and vanishing edge of Louisiana’s coast, where he used to work out of a trailer.

Back then, in the 1980s, Louisiana’s land loss crisis was just beginning to gain wider notice, and the young scientist eventually found himself on the front lines. At 34, Boesch became the first director of a new institute, the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium, and the state's coastal challenges would become a growing part of its broad mission.

“These days in Louisiana, I don't think you can be seen as not doing something for the coast,” Boesch said during a recent visit back to Cocodrie after taking in the view from one of the consortium’s windows, raised fishing camps and bright green marsh in the distance, holding out against the approaching Gulf of Mexico.

Advocating for the coast has become standard for Louisiana politicians, but it is no longer enough, as Boesch and other experts point out. With the effects of climate change and money shortages to deal with it closing in on south Louisiana, recognizing the causes and tackling them will be vital, too, they say.

Donald Boesch in 1986, during a tour of LUMCON with Interior Secretary Donald Hodel.

The threat will be unsparing, from the bayous of Terrebonne Parish, where the tiny fishing community of Cocodrie is located, to suburban St. Tammany, whose population has exploded despite carrying some of the state’s heaviest flood risks.

Boesch, now 78, has since gone on to a long list of scientific achievements, recognized nationally for his work, but the native of New Orleans’ 9th Ward still worries over the troubled future of Louisiana’s coast.

Cocodrie is 70 miles to the city’s southwest, and the drive down is filled with stark reminders that the state is losing its battle to keep the sea at bay.

The road passes dead oaks and their warped, withered limbs, killed by too much salt water moving inland. Wrecked buildings remain from 2021’s Hurricane Ida.

The scientists now working out of the marine consortium building whose construction Boesch saw through have a requirement that he did not: They carry boots in their cars — not for field research, but because the parking lot floods regularly, mainly due to the sinking land.

Donald Boesch stands on the marsh walk at the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium, where he formerly served as director, in Cocodrie, La., Friday, April 7, 2023.

For Boesch and others, the future is not hopeless, but a realistic approach is required. It’s “about buying time” — staving off the inevitable rising seas and disappearing land for as long as possible to be able to adapt, he says.

That means a real commitment to transitioning from oil and gas, both globally and in Louisiana, to limit rising seas. Carbon capture and storage, which the state has made a key part of its policy, can’t alone solve the problem, says Boesch.

A severe money shortage on the horizon as funding related to the 2010 BP oil spill runs out will also drastically limit the state's ambitious coastal master plan if new revenue is not found.

The academic, wearing a baseball cap over his white hair and closely cropped beard, points to projections of sea-level rise over the next century or so showing much of south Louisiana inundated. Without action now, it will be too late for his grandchildren to meaningfully slow the sea’s march, he says.

“It will be in a state where it’s unstoppable,” warns Boesch.

‘Resort-style’ with water slides

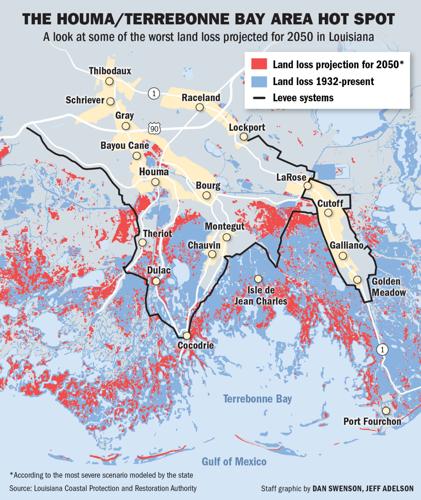

The risks of land loss, rising seas and intensified storms to places like Terrebonne Parish may be obvious from a glance at the map, its land fading into cloud-like wisps as it approaches the Gulf. Canals, including those built for oil and gas production, have also sliced and diced its wetlands.

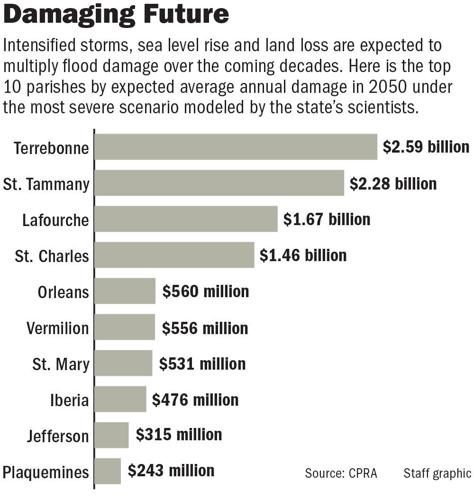

But the dangers are by no means limited to such locations. Perhaps less understood, for example, are the vulnerabilities of one of Louisiana’s fastest-growing parishes: St. Tammany, where projected flood damage over the coming years is Louisiana’s second-highest, trailing only Terrebonne, state data shows.

To put that into perspective, it helps to zoom out. By 2050, under the most severe scenario modeled by the state’s scientists, over 800 more square miles of land could be lost in Louisiana, on top of the 2,000 square miles since 1932. The number then climbs to more than 3,000 additional square miles by 2070, or around 7% of the entire land area of the state.

That amount of land loss can lead to lots more devastation, especially when combined with stronger storms and rising seas.

Average annual flood damage for Louisiana as a whole by midcentury could total between $4.5 billion and around $12 billion. Terrebonne’s projections range up to $2.6 billion under various scenarios, while St. Tammany is not far behind at $2.3 billion.

Unlike many vulnerable areas along Louisiana’s coast losing population, St. Tammany has been growing at a fast clip for decades, undergoing a rapid transformation from a collection of rural outposts to fully fledged suburbs. Its population has expanded by 38% in this century alone, thanks mostly to its image as a safe haven for residents fleeing the crime, poor schools and poor infrastructure of the city. It’s now the state’s fourth most populous parish.

The draw of building in view of the lakefront and its picturesque sunsets, not to mention St. Tammany’s scenic rivers, will no doubt remain strong. A multilayered plan is being developed by the Army Corps of Engineers to reduce flood risk for the parish — at a cost of some $4 billion — but when or if it can be built is far from clear. Either way, neighborhoods near the water will remain at risk.

It raises the question of whether more communities will attempt to take flood protection into their own hands — as one development near Lake Pontchartrain in the Slidell area has done.

The Lakeshore Villages subdivision, with its newly built suburban-style homes, ring levee and water slides, stands in sharp contrast to the elevated fishing camps and marsh next to it along Old Spanish Trail, the two-lane road leading to the Rigolets. The large lighthouse-like entrance to the neighborhood is unmissable from Interstate 10.

African American families have in particular gravitated to the subdivision, now being developed by DR Horton, the large Texas-based homebuilder. It labels the subdivision “resort-style,” and residents pay fees on top of their mortgages and parish taxes for infrastructure, maintenance and upkeep in the largely self-contained development.

The arrangement is known as a “community development district,” and while they remain rare in Louisiana, they are more widespread in states such as Florida, said the district’s manager Pete Williams, who runs a consultancy that specializes in them.

Annual fees depend on the size of the lot, but the most anyone pays is currently around $1,560, he said. That covers infrastructure such as the levee, drainage and roads. A separate fee pays for amenities and recreational areas. Houses are not raised, but Williams says the grade was built in accordance with the drainage plan.

The development is protected by a levee in the range of 18 feet, unlike nearby areas. It also has its own pumping station, along with canals to manage drainage.

Louisiana may be the state most at risk from climate change, and the year 2050 could prove to be an inflection point as seas rise and more lan…

Around 1,600 homes are now occupied in the development, still far short of the planned 3,000 or so. Williams and residents point to the convenient location near the twin spans, close enough to commute to the city with relative ease.

“You can go from that urban environment to have that kind of availability and housing in what I would consider a reasonable timeframe from a transportation standpoint,” Williams said. “And I think that's part of the allure, because you could work in the city.”

But there are drawbacks, starting with the additional costs to residents. Lakeshore Villages has also experienced complications, having defaulted on a 2007 bond issue for infrastructure under the original developer, Tammany Holding Co.

Williams was not associated with the development then, but said he suspected the troubled housing market surrounding the 2008 financial crisis may have played a major role. He also argued it should not cast a shadow over such development districts more broadly.

Stephanie Montgomery, 42, said her family was attracted to the family atmosphere and the prospect of living near water. She and other residents said the subdivision has had no flooding issues.

The atmosphere has lived up to her expectations, but she said her house had trouble with mold that took time to address.

Louisiana 2050: Rising sea levels will upend life and bring new risk to the state over the next few decades.

Environmental reporter Mike Smith talked to people on the frontlines of Louisiana coastal change. Robert "Robbie" Campo, of Campo's Marina in Louisiana, has seen a lot of change since he was a kid growing up in Shell Beach.

“I do recommend it as far as somebody looking for family-oriented homes,” she said. “But I’m always cautious in recommending it because of the builder issues.”

D.R. Horton did not respond to requests for comment.

John Lopez, a Slidell resident and coastal scientist formerly with the Pontchartrain Conservancy, is not closely familiar with the Lakeshore Villages levee, but said any such construction must take into account the effect on surrounding areas. He does not rule out others carrying out similar projects and said that should raise “regulatory concerns.”

“Levees don’t make water disappear,” said Lopez. “It just pushes it someplace else.”

An analysis by the First Street Foundation, a nonprofit that gauges climate risk, points to particular vulnerabilities in St. Tammany. As one example, it notes that Madisonville, nestled next to Lake Pontchartrain and the Tchefuncte River, faces what it classifies as “extreme risk” of flooding over the next 30 years.

It has also found that Lacombe, Covington and Eden Isles were among the areas in Louisiana with the widest gap between their estimated flood insurance premiums and average expected annual loss — meaning their risks far outweigh their current premium price. That may change as the federal government phases in Risk Rating 2.0, a new algorithm that aims to price flood insurance more accurately.

‘A path forward’

The LUMCON building in Cocodrie resembles a small airport terminal, complete with a tower where visitors and staff can take in sweeping views of the bayous and canals cutting through cordgrass marsh. The consortium now has a fleet of vessels allowing for wide-ranging research holding importance for Louisiana and beyond.

Donald Boesch stands outside the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium as he talks about his time as its executive director in Cocodrie, La., Friday, April 7, 2023.

The wider Terrebonne Basin surrounds it, its wetlands badly eroded and subsided over the last century due to the lack of sediment that once replenished them, sinking land, saltwater intrusion and oil and gas production. The state recently rebuilt three barrier islands in the basin, amounting to more than 1,000 acres, at a cost of $166 million.

Terrebonne Parish is projected to see Louisiana’s largest amount of land loss by 2050 under the most severe scenario modeled by the state’s scientists — up to 293 square miles, or more than double the number for Plaquemines Parish, which has the second-highest amount.

In his old office at LUMCON, Boesch and current director Brian Roberts looked at a map from the late 19th century showing land that once existed, pointing out the drastic changes in Terrebonne Bay and Timbalier Bay. He notes the barrier islands washing away.

“They used to say they used to run cattle along the ridge, out to the barrier islands,” Boesch says, noting the impossibility of that now.

A special report from The Times-Picayune | The Advocate examines Louisiana's perilous future in a time of rising seas and intensifying storms.

A former Fulbright scholar and Tulane graduate, Boesch left a job at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science at the College of William and Mary to return to his home state as the founding director of LUMCON in 1980. It began with him working out of a trailer before the building was constructed.

“My wife cried for like three months,” he said with a laugh.

When they left after a 10-year stint, their daughter by then at home there, his wife cried again — this time not wanting to leave, Boesch said.

He ended up at the University of Maryland, where he eventually served as president of the Center for Environmental Science. Along the way, he’s been drawn back to conduct influential work and research related to Louisiana.

That has included being appointed by President Barack Obama to a national commission on the causes of the 2010 BP oil spill. During a stint with the National Academy of Sciences, he helped develop a plan for a wide-ranging study to examine issues related to the lowermost Mississippi River, including land loss in the Bird Foot Delta at the river’s mouth. A major initiative was recently announced to do just that.

On his recent visit back, including over a shrimp po-boy at Coco Marina down the road from the LUMCON building, he spoke of tangles with Louisiana politicians and delved into explanations of land subsidence throughout the area.

He also suggested that a “truly courageous one-term governor in Louisiana” could tackle climate change and related coastal issues head-on, making the case that it affects not only the environment, but “our way of life and how we make money.”

But he said simply scaring people won’t work.

“There's nothing to be gained by fear and hopelessness,” Boesch said. “So you have to do it in a way that gives people a path forward about what they can do to make it less bad or better.”

Data editor Jeff Adelson contributed to this story.