On the fourth floor of Children’s Hospital, kids attached to IV bags rolled into a corner of the hematology oncology unit. On the window hung a sign: Children’s Hospital New Orleans welcomes Jon Batiste!

“Where is he?” asked a little boy with his face painted like a reindeer dog.

'American Symphony' chronicles extraordinary year in musician's life

Batiste was back in his hometown of New Orleans for a red carpet premiere of the new Netflix documentary "American Symphony" at the Orpheum Theater on Thursday night. The film chronicles the year in which Batiste wrote a symphony and enjoyed a series of career triumphs while his wife, author Suleika Jaouad, received a cancer diagnosis and began the grueling process of receiving a bone marrow transplant.

But the reindeer dog, a patient named Noah Calles being treated for Hodgkin's lymphoma, wasn't looking for Batiste. “Where is Emmett?” he asked.

When Emmett Richards, a blood cancer patient with green dragon face paint, finally arrives, the boys do normal kid things. They share stickers, eat chips and snap selfies of each other. It’s one of the most social interactions Emmett has had with other kids since his acute myeloid leukemia diagnosis in September, his parents said.

Some of the children do know who Batiste is. “He’s a famous person,” said Calles. “He sang on a Disney movie.”

Jon Batiste visits Children's Hospital New Orleans on Thursday, December 7, 2023. (Photo by Chris Granger, The Times-Picayune)

By 2 p.m., Batiste walked in to applause from the adults present, but had to compete for the kids' attention, some of whom had wrangled a parent’s phone to play games.

Then Batiste's fingers hit the keys.

Ava Rollins, a quiet 4-year-old with leukemia whose round eyes peeked over a tiny mask, quickly bounded off her chair and stood by Batiste while he played "When the Saints Go Marching In."

Batiste handed her, Emmett and Noah melodicas, an instrument “like a harmonica and keyboard put together,” he explained. The phone games were abandoned. Noah balanced his melodica on his IV pole. Together, the instruments produce a sound like a less-piercing bagpipe. Batiste belted out a whooping “Yeah!” when they got the hang of it.

“We have a band now,” Batiste said.

It was a moment of child-like normalcy for the young patients, as they banged on instruments to simply delight in the noise they made, even if it was with one of New Orleans’ most famous musical talents. Some of them have been in the hospital for months. Many of their lives, like Emmett's, hinge on a stem cell transplant.

“You don’t know what’s next,” said Emmett’s mom, Joycelyn Richards. “It’s just day by day.”

Finding a match

For kids like Emmett with high-risk acute myeloid leukemia, it’s not a matter of if, but when they will need a stem cell transplant. But good matches are hard to find.

Patient Emmett Richards, 6, laughs as he plays the melodica that Jon Batiste gave him during his visit to the hematology and oncology inpatient unit at the hospital on Thursday, December 7, 2023. (Photo by Chris Granger, The Times-Picayune)

Around 30% of patients in need of a transplant find a matching donor in their family. The remaining 70% enter a national registry hoping an altruistic stranger with similar ancestry has swabbed their cheek and entered the donor pool.

Last year, the Be the Match Registry facilitated nearly 7,000 bone marrow transplants, which are also called stem cell transplants. The need was about twice that, according to CEO Amy Ronneberg. That's why Batiste and his wife are working with the registry and other partners to increase the list of donors and improve access to transplants, especially for people in ethnically diverse communities. A stem cell donor registry drive was also hosted Thursday at Children's.

Musician Jon Batiste, right, takes a selfie with Xavier students in the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity who helped lead a drive at their school for the Be The Match registry. Batiste visited Children's Hospital New Orleans on Thursday, December 7, 2023. (Photo by Chris Granger, The Times-Picayune)

Depending on a person’s ethnic background, the chance of finding a match is between 29% and 79%, according to Be The Match. For people of color, the odds of a good match are much lower, because the donor pool is small. That means the match isn’t always as close as doctors would like it to be, and that can lead to more complications, said Dr. Benjamin Watkins, pediatric hematologist oncologist.

Avery Mullen, 5, plays the melodica that Jon Batiste gave her and other patients during his visit to Children's Hospital New Orleans on Thursday, December 7, 2023. (Photo by Chris Granger, The Times-Picayune)

In that sense, Jaouad, a mixed-race person, was fortunate to have her brother as a match when she first was diagnosed with cancer at 22. But sometimes, even if a family member is a match, an outside donor is preferred. Certain cancers and diseases may run in families, giving a greater chance of reoccurrence with a family match.

That was the case when Jaouad’s cancer returned at the end of 2021, over twelve years since her first diagnosis. But with no match in the pool, her brother again donated stem cells. On the same day Batiste received 11 Grammy nods, Jaouad began her first day of chemotherapy.

For the patient, finding a match is just the beginning. They then undergo taxing chemotherapy to wipe the bone marrow clean before transfusing the donor cells.

The process is comparatively simple for the donor. It's typically a straightforward procedure that involves removing the blood, similar to blood donation, taking out the stem cells, then returning the blood to the donor.

Easing the pain

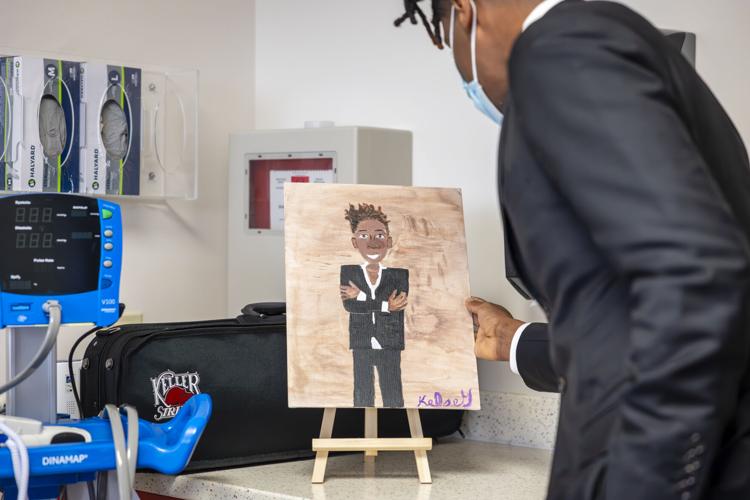

For patients like 11-year-old Kelsey Farris, who has sickle cell disease, a donor means the chance at a life without pain. Pain episodes, which she’s had since she was 11 months old, feel like “getting stabbed in the back 1,000 times,” she said.

Jon Batiste can't believe Children's Hospital New Orleans patient Kelsey Farris, 11, of Marrero, gave him a painting that she drew of Batiste as a thank you for his visit to the hematology and oncology inpatient unit at the hospital on Thursday, December 7, 2023. (Photo by Chris Granger, The Times-Picayune)

Farris spent the last two days making a portrait of Batiste to give him when he arrived. Because she’s extremely immunocompromised, she couldn't leave her room. Batiste made a special stop to say hello and sign her violin. When he left, a single tear ran down her face.

Farrris got her transplant a month ago and has been in isolation in the hospital since, but expects to go home any day. All she knows about her donor is that she’s a 27-year-old female in the U.S.

The transplant has been hard, and recovering in a hospital room she can’t leave isn’t easy. When they told her she would lose her hair, the fifth grader said she got emotional.

“But I just chopped it off and got back to the important stuff, like the medicine and all of that,” said Farris. “But it was a journey, and I got through it alive.”